On a cold January morning, Jonas Peacock was startled awake as nurses rushed to gather his belongings in his Sacramento nursing home. They tossed his clothes and toiletries into bins.

It was 4 a.m. and they were sending him away.

“I didn’t brush my teeth or nothing. They threw a pair of sweatpants on me, a t-shirt, my shoes, and put the sling on me so they could put me in the gurney,” Peacock said.

EMTs loaded him into an ambulance. He didn’t know where he was headed.

Peacock left prison in 2020 after a spinal infection left him unable to walk. He was living at the Sacramento facility, Asbury Park Nursing and Rehabilitation Center, through a program called medical parole.

After a 400-mile drive, the ambulance pulled up to its destination: Golden Legacy Care Center in the San Fernando Valley.

One month earlier, the federal government revoked Golden Legacy’s certification. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) deemed it one of the most troubled facilities in the nation. Inspectors visiting the facility had documented serious issues, including a resident cuffed to a bed and several violations of patient care.

Now the decertified facility would house Peacock — and nearly every other California medical parole patient.

Peacock’s transfer, and that of dozens of others on medical parole across California, was triggered by a standoff between the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and federal health regulators over the rights of people under state supervision.

CMS has stated that patient rights — including the rights to be free from physical restraints and to receive visitors — extend to all nursing home patients, including those involved with the justice system.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation maintains that restrictions on medical parolees are necessary to ensure public safety. People in the program have been convicted of serious crimes, including rape and murder.

Keep up with LAist.

Medical parole patients are among the most vulnerable in the state’s corrections system. The program was intended to help with overcrowding and lower the costs of caring for chronically ill patients, in part, by shifting costs from the state to the federal government.

To qualify, incarcerated people must have a condition that makes them “permanently medically incapacitated,” and unable to perform one or more basic functions of daily living. Patients include paraplegics, quadriplegics and stroke patients. California’s Board of Parole Hearings rules on each case.

'California Has Let Them Down'

LAist pored through documents and databases that shed light on the changes to the medical parole program and Golden Legacy. The consolidation of patients at a single facility, and one with a troubled track record, concerned family members, advocates and lawmakers who spoke to LAist.

Peacock said he has called the state four times to make complaints at Golden Legacy, something he never did at his previous nursing home.

“The first time because it was my third time being left sitting in feces and urine for hours — I mean, like three to four hours,” he said. “The next time was because one morning, I woke up at like 5 a.m. and I was in extreme pain in my groin area all the way to my bladder, and I asked them to take me to the hospital. And they refused.”

CDCR did not respond to several requests for an interview, but answered questions by email. Spokesperson Vicky Waters wrote that the agency is “committed to the health and well-being of both our incarcerated and parole supervision patients by ensuring a constitutionally mandated community standard of care is provided, regardless of where the individual is housed.” Waters said the agency didn’t have enough specifics to respond to claims medical parole patients made about their care.

Golden Legacy’s administrator and representatives of its parent company, Golden State Health Centers Inc., did not respond to several requests for comment.

“These are incarcerated people with serious medical needs, who are really caught in the crossfire between the state and the federal rules. And that's through no fault of their own,” said Leah Daoud of UnCommon Law, which provides legal representation to people navigating parole. “California has let them down.”

A Prison By Another Name

The incarcerated patient at Golden Legacy was cuffed to his bed by his ankle, nearly 24 hours per day. Correctional officers watched over him round the clock. And yet he couldn’t move on his own.

Regulators were alarmed to discover the patient during a routine inspection at Golden Legacy last summer. They wrote that the nursing home allowed the resident to be “restrained by handcuffs without medical justification … worsening pressure ulcers which required hospitalization.” They cited the facility with the most serious federal violation, an "Immediate Jeopardy."

Golden Legacy failed to protect the resident from neglect, regulators said, by “enforcing the policies and rules imposed by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.” CMS guidance says nursing homes aren’t meant to be correctional facilities.

“That doesn’t sound like you’re creating a skilled nursing facility there. It sounds like you're just trying to create a prison by another name,” said Dan Mistak of Community Oriented Correctional Health Services, an Oakland-based group that monitors healthcare that incarcerated people receive.

Inspectors had previously documented an incarcerated person cuffed at a nursing home outside Modesto in 2019. Inspectors there found a resident who was shackled on both ankles, despite being in a “persistent vegetative state.”

The person who was cuffed at Golden Legacy was not on medical parole, CDCR’s Waters said, but an “inmate patient,” an incarcerated person who requires a level of care not available in state prison.

Regulators also found other violations of CMS requirements related to the care of several other patients at Golden Legacy who were on medical parole. Five patients under CDCR supervision “could not move around freely” without a GPS device on their ankle or wrist. Others couldn’t receive visitors of their choice or have cell phones or computers. Inspectors wrote that the residents “were at risk of decline in physical, medical and psychosocial conditions.”

Regulators also found an infestation of cockroaches in the kitchen. The insects were seen crawling on the walls and scurrying under a dish machine draining board. The infestation was so widespread that a pest control technician recommended throwing out the refrigerator five months earlier “due to cockroaches ‘being deep within the fridge." Elsewhere in the kitchen, regulators documented a “large, expired turkey breast” and that food in the freezer had thawed and was “soft to touch,” and the bottom of the freezer had a “black color liquid.”

All together Golden Legacy racked up seven Immediate Jeopardies. Regulators imposed a hefty fine of $12,360 per day for a week, and denied Medicare and Medicaid payments for any new patients.

It was hardly the first time Golden Legacy had been flagged by regulators. In fact, for more than four years, the nursing home was a fixture on CMS’s Special Focus list, a designation for facilities with a track record of poor care.

“That's a long time,” said Tony Chicotel, an attorney with the California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform. “The idea of the Special Focus Facility program is that you will spend a year or two getting the special attention of CMS and if you haven't turned things around, you better have a very good reason or you're going to get decertified.”

In November, CMS sent Golden Legacy a “termination notice,” declaring that the facility would no longer be able to accept Medicare or Medicaid payments.

CMS declined an interview. An emailed statement said the agency “terminated the provider agreement with Golden Legacy due to the facility’s inability to come back into compliance with federal regulatory requirements for long term care facilities,” which included patient rights and infection control violations.

The facility remained licensed by the California Department of Public Health, which meant that it could continue to accept patients, so long as the patients did not receive Medicare or Medi-Cal. The public health department did not respond to a request for comment about the licensing. But Golden Legacy’s situation meant CDCR could place incarcerated patients at the facility without violating CMS guidelines.

CDCR spokesperson Waters said the patients were moved to Golden Legacy so they wouldn’t have to be returned to prison.

"This is a challenging issue, and we are taking the best approach we are able to in order to ensure patients on medical parole who require housing in a skilled nursing facility have a place to go to get the care they need, and where we can still fulfill our commitment to public safety.” Waters said. “The CMS issue has severely limited where we can send these people, and that’s basically the reason we have placed 50+ medical parolees, whose custodial case factors require them to have restrictions, at Golden Legacy recently.”

Key Details Shielded From The Public

Losing payments for Medicare and Medi-Cal patients would shut down most nursing homes in California. Not Golden Legacy.

The single-story, 204-bed Golden Legacy Care Center belongs to a broader network. The facility’s license is held by an entity called San Fernando Subacute Rehabilitation Center LLC. Martin Weiss is listed in state records as the entity’s owner, and public records show he has an ownership stake in at least six other nursing homes across the state.

Weiss, an attorney for his business, and Golden Legacy’s administrator did not return requests for comment. LAist reporters were unable to reach the administrator when they visited Golden Legacy.

Weiss’s company, Golden State Health Centers Inc., took over the operations of the facility in 2019 after the previous owners declared bankruptcy. The previous owners struggled to provide adequate care, and debts “began to mount as a result of the continuous imposition of penalties and fees” for patient care violations, according to a filing from the bankruptcy case.

As private business entities, details about the organizations affiliated with Golden Legacy are difficult to obtain. But state disclosures offer indications that, even prior to the decertification, Golden Legacy had a different business model than many other skilled nursing facilities.

An LAist analysis of financial reports filed in Jan. 2019 found that the median California nursing home received 78% of its revenue from government sources. Golden Legacy only received 20% of its revenue from Medicare and Medi-Cal, according to its 2020 financial disclosures, the most recent available.

The facility reported $27 million in revenue for 2020, with $8.1 million of that coming from Medicare and Medi-Cal.

Taxpayer money pays for the care of medical parole patients, yet Golden Legacy’s contract with CDCR is shielded from public view, an uncommon provision for government contracts. The payment rates in the agreement between CDCR and Golden Legacy will not be available to the public until 2026.

That’s due to an obscure 1995 law that keeps details about CDCR’s healthcare contracts exempt from disclosure for up to four years.

Charlene Harrington, an emeritus professor at University of California, San Francisco, said very few nursing homes operate with state licenses but without CMS certification, as Golden Legacy does. Those that do are often facilities that take wealthy private payers, who don’t rely on Medicare or Medicaid funding.

When a nursing home is decertified, the state licensing agency often moves to de-license a facility as well, she said.

“If it's not good enough for older people, to have this owner, but it's good enough for prisoners — I don't think that's a very good statement to be making,” Harrington said.

Next door to Golden Legacy sits another nursing home, Sylmar Health and Rehabilitation Center, which is also owned by Golden State Health Centers.

The psychiatric facility contracts with another state program that handles conditional release and is run by the California Department of State Hospitals. The program, CONREP, provides outpatient care for people found incompetent to stand trial, who were found not guilty by reason of insanity, who are “mentally disordered” or are, in some cases, on parole. Ringed by tall perimeter fencing, Sylmar currently has a 24-bed unit for people in the program.

Golden Legacy also has a contract to house CONREP patients, with a value of as much as $12.7 million. The contract says the facility will “provide services for a seventy-eight (78) bed locked unit comprised of three wings with three enclosed and secured courtyards.” It has a start date of Jan. 1, 2020, but a Department of State Hospitals spokesperson said that the program “has yet to activate” due to delays with licensing and construction.

Life At Golden Legacy A 'Step Backwards'

For many, medical parole is the latest step in a long journey through the justice system.

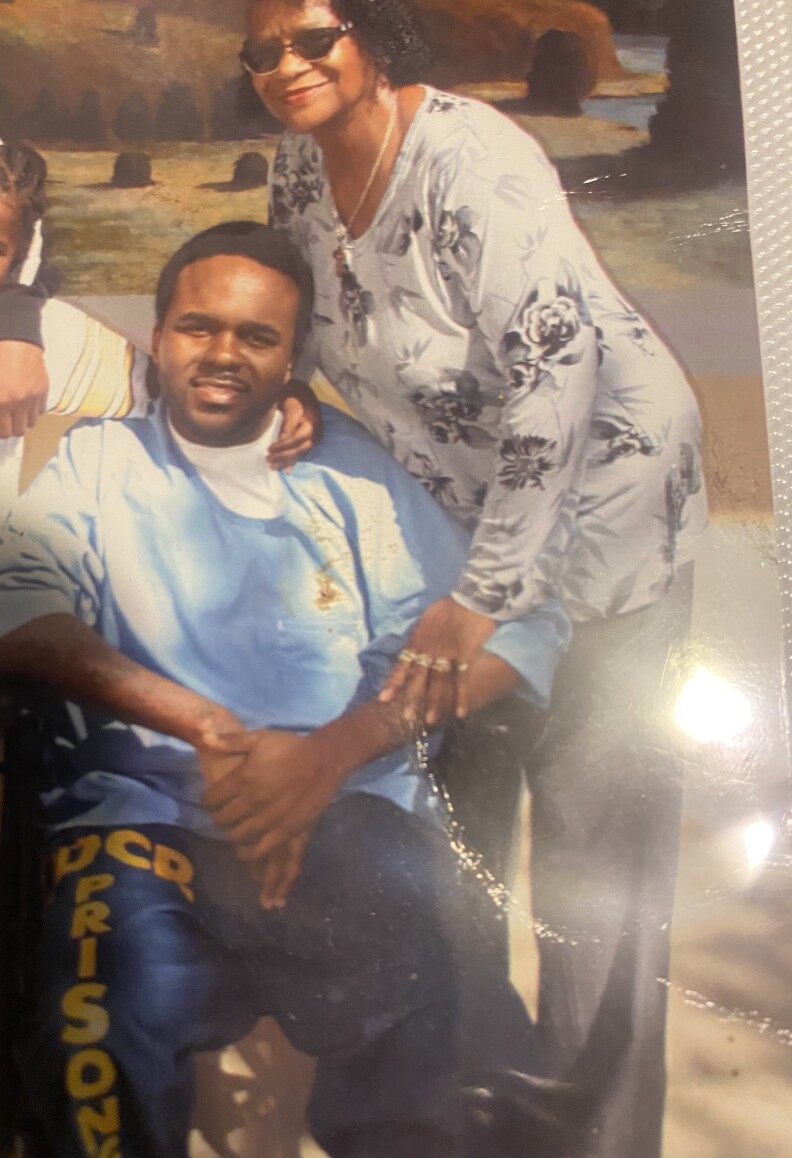

Peacock was sleeping in his cell in Salinas Valley State Prison in 2019 when he lost feeling from his neck down. “I woke up and I couldn’t move,” he recalled.

He was taken to a hospital, he said, where doctors found a severe spinal infection. He could no longer walk. Peacock applied for medical parole and was approved in April 2020. That’s when he was released to Asbury Park in Sacramento.

After serving nine years in prison for an involuntary manslaughter conviction, it was a dramatic change of scenery.

Peacock uses a wheelchair, but needs help operating it. He can barely use his hands — his left arm is atrophied and his right wrist is dropped.

“My body won’t go where I tell it to go, it’s like it just doesn’t want to respond,” he said.

Since moving to Golden Legacy, Peacock, 39, says he hasn’t been able to get the same physical therapy he did at Asbury Park. He depends on nursing staff for basic needs like being transferred to bed, but said he’s endured long waits for help.

Donna Maxwell, Peacock’s mother, was devastated when she heard that her son was transferred to Southern California.

Maxwell lives in Vallejo, about an hour’s drive to Asbury Park. To Los Angeles, it’s about six. She said she can’t afford to visit often, and that she’s had surgery on her lower back that makes driving difficult.

“I don't think that it's right that you move families where their family member has a hardship of visiting them,” she said.

Harrington from UCSF agreed. “If they're moving them away from their families, then there's going to be no family oversight,” she said.

I don't think that it's right that you move families where their family member has a hardship of visiting them.

Waters, of CDCR, wrote of Golden Legacy: “While the facility is not CMS certified, it is licensed to operate in the state, and [corrections healthcare services] has a long-standing working relationship that has allowed us to monitor and ensure patients are receiving the care they need.”

“We continue to look at all options in regards to placement for expanded medical parole patients,” she added.

The transfer to Golden Legacy has been a struggle for many on medical parole. LAist spoke to nine of them. Common complaints included long wait times after ringing for help, a lack of specialized services, and staffing shortages. In 2021, Golden Legacy requested and was approved for a “workforce shortage” waiver from the California Department of Public Health, allowing the facility to staff below the minimum requirements for nurses and nurse assistants.

Harry McBride, 76, who is paralyzed from the waist down and blind, said he was transferred to Golden Legacy from Richmond Post Acute Care Center without any prior notification. “They didn’t give me no warning whatsoever,” he said.

McBride said that during the move, he lost his radio, batteries, and headset for his book reader.

McBride said he’s had six heart attacks. He believes he received quality medical care at the Richmond facility.

During one heart attack, a correctional officer found him in his cell. “[He] came and asked me a question and I was white as a sheet and totally incoherent, and in five minutes he had me downstairs in an ambulance … If he didn't show up inside the room to ask me a question, I would have been dead,” McBride said.

But he does not trust that would happen at Golden Legacy.

“When I hit the call light, it’ll take hours for somebody to show up,” he said. “I keep telling them if I have another heart attack, and if I have to wait five hours for someone to stick their head in to find out what’s wrong, I’ll be dead.”

Others who spoke to LAist said the environment at Golden Legacy doesn’t feel like parole. “It’s more like an annex to the prison system,” said Danny Cohea.

Cohea, 63, was transferred from Boulder Creek Post Acute, a nursing home in San Diego County. He was granted medical parole in 2020 after he says tumors in his spine left him paralyzed from his mid-chest down. Cohea had spent 27 years in prison, and recalled his first days on medical parole.

“Every day was locks and bolts and [you] can’t move without cuffs and can’t move without leg restraints and all that. All that disappeared. There were no correctional officers around,” he said. “It wasn’t like being free — I can’t go as far as saying that. But it did feel like a bunch of the restraints on me [were] relieved and removed.”

At Boulder Creek, Cohea lived with the general public and would socialize with residents in the cafeteria or the therapy room.

“[Golden Legacy] seems like a step backwards for us,” he said.

The Past And Future Of Medical Parole

Like California, nearly every state prison system has release programs for incarcerated people who are elderly or severely ill, according to FAMM, a nonprofit that advocates for criminal justice reform.

“Continuing to incarcerate such people behind bars and barbed wire is inhumane,” said Mary Price, an attorney with FAMM. “It's expensive for the state and it doesn't further our interest in the ends of punishment.”

In Connecticut, a nursing home has been able to serve residents involved with the justice system while continuing to receive Medicaid and Medicare funding. Mike Landi, chief operating officer of the iCare Health Network, which operates 60 West, said the facility was not initially certified by CMS, but eventually received it.

Landi said it's imperative to treat justice-involved patients no differently than other residents. All residents at 60 West have the same access to phones and visitation. “We don't do anything different in this facility than we do in our other facilities,” he said.

About one-third of 60 West’s 90 residents are justice-involved and may have parole conditions, Landi told LAist, but the facility’s staff are not involved in those restrictions.

“That's something that's worked on between the parole officer and the resident directly,” he said. Unlike California’s model, he said the nursing home does not have a direct contract with the state corrections department.

Former State Sen. Mark Leno authored legislation that created California’s medical parole program in 2010. The program expanded in 2014 under an order in the landmark prison overcrowding lawsuit.

Between 2011 and Sept. 2020, the state granted medical parole to 183 people. “That is a much more conservative number than we had hoped,” Leno told LAist.

He was alarmed by the recent changes to medical parole in California. “It is counter to the other motivation for our bill, which was to return people closer to their communities and to their families in their last months of life, not to ship them off to a substandard care facility in Los Angeles.”

The number of people receiving medical parole rose dramatically in 2021, the second year of the pandemic. Last May, 76 patients were receiving medical parole, the highest monthly figure in six years of data reviewed by LAist. The numbers have declined since.

The changes to medical parole come as the population of older Californians in prison has spiked.

The most recent CDCR data available, from 2019, shows that people 55 and over make up 16% of the incarcerated population — nearly double the population between 18 and 24 in state prison. In recent years, the share of older Californians in prison has steadily risen, and California prisons have the highest health care costs in the nation per incarcerated person, according to a Pew review in 2017.

It is counter to the other motivation for our bill, which was to return people closer to their communities and to their families in their last months of life, not to ship them off to a substandard care facility in Los Angeles.

Medical parole in California is open to incarcerated people of all ages. But many of those whose cases were reviewed by LAist were in their 60s, 70s or 80s. No one serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole, or who has received a death sentence, is eligible for medical parole.

In Sacramento, state legislators are considering changes to the program. Assemblymember Phil Ting (D-San Francisco) has introduced AB 960, a bill designed to allow more people to become eligible. A version of the legislation from 2021 would have expanded medical parole eligibility to incarcerated people in debilitating pain, who qualify for hospice treatment, or who meet other criteria.

“I’ve been wanting to reform medical parole for quite a while,” Ting said. “These inmates are probably the most expensive inmates to care for.”

Ting told LAist he was “very concerned” about the recent changes to medical parole.

CDCR’s Waters wrote in an email that the agency hoped the current situation is a “temporary measure.”

For Maxwell, Peacock’s mother, ensuring quality care for her son and others at Golden Legacy is urgent.

“Whether [they’re] federally funded or not, they get paid,” said Maxwell. “And so for them to get paid, they need to take care of their patients … Even though they're prisoners, they’re still patients, and they're still people.”

CDCR has made one distinction amid the standoff with the federal government. In March, Waters wrote the agency “felt [it] should limit the new referrals to ventilator dependent patients to follow the residents’ rights and not impose conditions of parole.”

“Ventilator-dependent people do not have conditions or restrictions placed on them due to their medical condition, and can therefore be placed in any [skilled nursing facility] in the state,” she said. (Two people on medical parole remained at Somerset Subacute in El Cajon “due to long term ventilator status and the removal of conditions of parole,” Waters said.)

The agency did not provide details on the decision to remove parole restrictions for people on ventilators.

“It's an arbitrary distinction,” said Daoud, the advocate who has worked with incarcerated people. “The intention of the federal licensing rules — I don't think they intended for this kind of situation to happen.”

-

Reporters: Aaron Mendelson and Elly Yu

Editor: Kamala Kelkar

Radio editor: Adriene Hill

Visuals: Alborz Kamalizad

Map: Karen Wang

Community engagement: Paisley Trent

Web production: Brian Frank

-

The Jane and Ron Olson Center for Investigative Reporting helped make this project possible. Ron Olson is an honorary trustee of Southern California Public Radio. The Olsons do not have any editorial input on the stories we cover.