At a nursing home in Los Angeles last year, a nurse’s aide was giving a resident a bed bath when she noticed something moving around his feeding tube. When she looked closer, she saw maggots crawling from underneath the tube’s dressing.

Another nurse noted that the patient’s tube — inserted into his stomach to provide nutrition — “had not been cleaned” and “flies are always in the building.” There was no record of the feeding tube being cleaned for 23 days, a state inspector reported.

Already paralyzed from a stroke and suffering from COVID-19 pneumonia, the 65-year-old man contracted a serious infection and landed in the hospital.

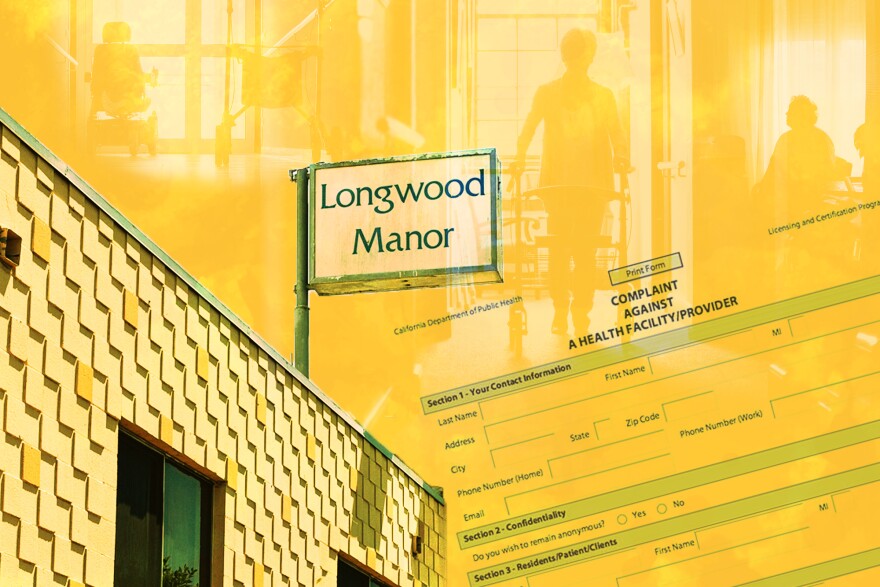

The California Department of Public Health, which regulates nursing homes, investigated and in September 2020 fined the nursing home $60,000, concluding that the patient’s care at Longwood Manor Convalescent Hospital was so deficient that it could have killed him.

But the nursing home’s operator, Longwood Enterprises, Inc., has sued the state to overturn the fine, saying the alleged violations were not serious enough to merit the amount, according to a complaint filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court last December.

Over the past 18 months, Longwood Manor, located in L.A.'s mid-city area, has sued the state four times in an effort to overturn fines and violations alleging poor care of its patients, according to court records.

The company’s lawsuits are among at least 433 appeals that nursing homes have filed against the state health department since 2016, according to a CalMatters analysis of enforcement actions. Nursing homes appealed more than 60% of the state citations involving a patient death and nearly half of the citations involving significant patient harm or threat of harm.

At Longwood Manor, in addition to the maggot case, the health department since 2017 has reported that a mentally-impaired woman was sexually abused by another patient, a resident repeatedly stabbed himself in the neck and required a trip to the emergency room, and a patient choked on a medicine cup and spent nine days in intensive care. The nursing home has a one star rating, out of a possible five stars, from the federal government.

The California Department of Public Health declined to grant interviews or discuss its process or criteria for deciding when to downgrade citations and fines.

In court documents for the maggots case, Longwood Enterprises called the state’s $60,000 penalty “arbitrary, capricious and lacking in evidentiary support.” Elizabeth Tyler, the company’s attorney, said she was “not in a position to talk about the facts” in the case, and described the other three incidents as unforeseeable. Tentative settlement agreements between the state and Longwood have been reached for three of the lawsuits, according to Los Angeles County Superior Court records.

The state health department settles many nursing home lawsuits, downgrading some of its most severe sanctions for deadly and dangerous incidents to less serious violations and lower fines, CalMatters’ analysis shows.

Between 2016 and 2020, the state downgraded and reduced fines of 14 of 45 citations involving the death of a resident after nursing homes sued, according to CalMatters’ analysis. Some of the facilities had chronically poor safety records. These “AA” citations carry fines of up to $100,000; two were slashed to $20,000.

State regulators also downgraded about 12% of “A” penalties — which involve actual or probable serious harm to patients — that nursing homes have taken to court since 2016. These violations carry fines of up to $20,000.

California is unusual in its requirement that nursing homes sue in civil courts to overturn citations and fines, due to a 1973 state law. Other states have state regulators or administrative judges handle appeals.

The California Department of Public Health declined to grant interviews or discuss its process or criteria for deciding when to downgrade citations and fines, and there are no public records on individual cases that explain their decisions. The department only provided an unsigned, emailed statement saying that its decisions are “based on the individual facts of the case” and information that emerges during appeals.

The maggots incident is a sign of a “systems breakdown, a violation of the right to quality care.”

The state has downgraded more than 600, or almost a quarter, of the more than 3,000 citations issued to nursing facilities over the five-year period for all violations, from the most serious ones involving deaths to records falsification, short staffing and data breaches, according to the health department’s statement.

A Nov. 19 court document indicates that a “settlement agreement is under final review” in Longwood Manor’s appeal of the state sanctions imposed for the patient who had a maggot-infested feeding tube. No additional information was included.

The maggots incident is a sign of a “systems breakdown, a violation of the right to quality care,” said Lori Smetanka, executive director of the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, an advocacy group.

Imagine, she said, “how that person and their family felt. There’s nothing okay about that. That [Longwood Manor] should be excused from that is really outrageous.”

Patient names in investigation reports are redacted for privacy, so it is unknown whether the patient survived the maggot-related infection.

The courtroom battles hold high stakes for nursing homes: their profits and even outright survival. State regulators have the authority to cut Medi-Cal payments or revoke the licenses of nursing homes that receive too many citations too quickly, just as drivers can lose their licenses after too many traffic tickets.

Nursing homes consider these fines and the legal costs of contesting them as “just the cost of doing business,” Smetanka said.

Suing the state is the only process that Longwood Manor and other nursing homes are allowed to pursue in California to appeal certain violations and fines, said Elizabeth Tyler, Longwood Manor’s attorney.

The lawsuits provide a “safeguard to ensure these serious allegations against health care providers are carefully evaluated,” she said. “The idea that just because you’re a nursing home you should take your lumps rather than explore defending your reputation” in court, “I find that troubling.”

As of mid-September, the state was defending 194 lawsuits by nursing homes. The companies do not have to pay fines until their appeals, which can take years, are exhausted.

The idea that just because you’re a nursing home you should take your lumps rather than explore defending your reputation (in court), I find that troubling.

Of the roughly $23.3 million in fines California has levied on skilled nursing facilities since 2016, about 25% remains unpaid, mostly from still-open cases.

Reports of problems in regulation of nursing homes and delays in penalties date back at least several years in California.

A 2018 state audit found that the state health department lagged in inspecting and citing facilities for violations and failed to ensure that they met quality-of-care standards. The average age of the pending investigations of violations nearly doubled between January 2019 and March 2020, according to an auditor’s update.

A New Law Takes Aim At Fines And Appeals

In 2008, a Marysville nursing home appealed a state “AA” citation after an 84-year-old woman with Alzheimer’s disease was found dead with her head stuck between her bed and a bed rail. An autopsy showed that her larynx had been compressed and fractured, according to the citation.

In the state’s report, a nurse inspector for the state agency wrote that the patient “who was totally dependent for all activities of daily living, choked to death on the side rail while she was unable to free herself.”

The nursing home appealed, and its attorney noted that the coroner had found the patient had a dilated pupil, a possible sign of a stroke that could have contributed to the patient’s death. Before a judge could rule, the California Department of Public Health settled the case by downgrading the citation from “AA” to “A” level and reducing the nursing home’s fine.

A new state law, however, is designed to make it easier for the agency to prevail in cases like this.

Sponsored by Assemblyman Ash Kalra, a Democrat from San Jose, and signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in October, the legislation raised nursing home fines — which hadn’t changed in about 20 years — by 20-to-50%.

It also changes how state regulators sanction nursing homes that were found to have caused the death of a patient — and then may have to litigate to defend those sanctions in court. Beginning Jan. 1, the state must demonstrate that the nursing home’s actions were “a substantial factor” in the resident’s death, rather than a “direct proximate cause.”

Kalra said the old standard allowed some nursing homes to evade accountability if they could show patients had other ailments that might have contributed to their deaths. The nursing home industry opposed the bill and previous versions of it.

The California Department of Public Health detailed in a letter to Kalra how the current law had hindered its efforts to hold nursing homes accountable for preventable deaths.

Because nursing homes often cite patients’ other serious medical issues when appealing citations for violations that resulted in death, “as a result, many of the violations that involve [a long term care] resident death are either issued as class 'A' instead of class 'AA,' and the facility receives a lower penalty, or a judicial decision is rendered that downgrades the level of the citation,” the agency wrote to Kalra.

The case involving the death of the woman in Marysville, Kalra said, is “a perfect example of how nursing homes escape culpability.”

Costly Fights Against Fines

COVID-19 thrust California’s 1,200 nursing homes into a spotlight, intensifying long-standing concerns about inadequate staffing and infection control and poor quality care. The virus has killed 9,355 patients and 250 staffers statewide.

About 400,000 Californians each year reside in skilled nursing facilities, which serve the most medically fragile patients, including people who need 24-hour-a-day nursing care and are disabled or suffering from a serious illness, and those recovering from surgery or injury.

Advocates for the elderly contend that nursing home operators are spending huge amounts of money on legal fights that would be better spent on improving patient care, and that California’s willingness to settle some cases just gives them more incentive to do so.

Defending the nursing homes’ lawsuits to overturn fines can be time-consuming for the California Department of Justice. These cases can take up to three years to wind through the courts.

Some nursing homes and the department are still fighting in court about citations first issued in 2016, according to state data.

“The labor and expense involved to go through Superior Court is extraordinary for the amount of money involved,” said Eric Carlson, directing attorney of Justice in Aging, an advocacy group.

“It doesn’t surprise me that the state chooses to settle some cases,” he said. “The burden of defending the citation is such that the state can make a cost-benefit analysis and choose to settle for pennies on the dollar.”

Fighting the fines can be costly for nursing home operators, too. They easily can spend more on legal fees than the state fines they’re appealing, which can range up to $100,000.

But with nursing home payments tied to quality ratings, the homes have a financial incentive to appeal as many citations as possible. Citations can lower a home’s rating on Medicare’s Care Compare website, which families, hospitals and insurers use in assessing nursing home quality.

The burden of defending the citation is such that the state can make a cost-benefit analysis and choose to settle for pennies on the dollar.

Sanctions for severe lapses of care also can preclude homes from seeking leniency on state staffing requirements or receiving state quality bonuses that can top $500,000, said Mark Reagan, an attorney who represents nursing homes and serves as legal counsel to the industry group California Association of Health Facilities.

“I’ve had cases over the years where the operator knows it’s going to cost more money to pursue the case than the fine, but it’s more important … to not have something on their record that the general public can see that they don’t think is fair,” Reagan said.

Citations do appear on state and federal nursing home enforcement websites while they’re being appealed, but are updated if they are downgraded, Reagan said.

Decades ago, California was known for its leadership in nursing home enforcement.

The state has robust nursing home health and safety standards that served as a national model, Carlson said. As a result, most other states simply enforce federal standards, while California puts more energy into enforcing state laws, he said.

That makes the nursing homes’ ability to appeal sanctions in Superior Court an important safeguard for the companies because it “evens the playing field and gives us a fair chance,” said Eric Emanuels, a Sacramento attorney who represents nursing homes.

In some cases, Emanuels said, the state issues a citation up to two years after an event. “It’s a great way to win those cases,” Emanuels said, because judges acknowledge that nursing homes can’t successfully defend themselves so long after the fact.

A Case Study: Dueling Lawsuits

In some cases, two lawsuits involving the same event are occurring simultaneously in the same courthouse — a resident sues a nursing home and the nursing home sues the state.

In May, state inspectors fined Longwood Manor $60,000 after accusing the company of failure to prevent a mentally-impaired woman from being sexually abused by another resident. The 37-year-old woman was taken to a hospital for a rape evaluation and given preventive treatment for sexually-transmitted diseases, the citation noted.

Two months later, Longwood Manor’s operator sued the state health department to overturn the fine, saying the agency’s actions were “arbitrary, capricious and lacking in evidentiary support” — the same words it used to describe the maggots case.

Shortly after that, the patient’s sister, who was not identified, sued Longwood for the sexual assault, said her attorney, Art Gharibian.

The patient, known in the lawsuit only as “G.W.,” was vulnerable because of her many medical conditions, including brain damage, epilepsy, heart attack and a feeding tube, according to the lawsuit. The lawsuit alleges that the nursing home failed to protect G.W. from the assault.

Both cases are still pending.

Gharibian said he typically can’t use the state’s citation reports — appealed or not — to bolster his clients’ cases because they’re considered hearsay under a legal precedent known as the Nevarrez decision. Nursing homes will tell a judge that a citation is being appealed if patients’ lawyers try to use them to establish patterns of poor care, he said. He said they also sometimes use those appeals as leverage to get residents or family members to settle their lawsuits.

Longwood Manor is still battling one $20,000 state fine from 2018, in which a 80-year-old woman with diabetes and difficulty walking went missing from the nursing home in Los Angeles after failing to return from a routine afternoon outing to do errands. Instead of checking on the resident, who had lived there for five years, the nursing home discharged her after she didn’t return for three days and did not consider her a missing person.

Twelve days after leaving Longwood Manor, the woman was found dead in a storage unit in Pennsylvania on a night when the recorded temperature was 29 degrees, according to a state inspector’s report.

According to the report, a family member “stated that Resident 1 was found deceased in Pennsylvania on 3/16/18 by the owner of the storage unit and was only dressed in a hospital gown in the cold temperature weather.”

State regulators imposed a Class A citation on the nursing home, for, among other violations, not informing the family member of the woman’s absence and not investigating her absence or reporting it to the state.

Tyler, the company’s attorney, told CalMatters that the woman was considered self-responsible, meaning that she could make her own decision to leave the nursing home. A bench trial, postponed because of the pandemic, is scheduled for early next year.

Nursing homes have the right to appeal their citations, but this system seems more “beneficial to the facilities, not the victims,” said Carole Herman, founder of the Foundation Aiding The Elderly patient advocacy group.

Nursing homes are allowed a 35% “discount” if they don’t appeal an “A” or “AA” citation and pay their fines promptly. “If you get a speeding ticket, can you negotiate that? No.” Herman said.

Herman said the state’s sanctions are so long-delayed and watered down that they wind up failing to force nursing homes to protect their patients.

“Families are desperate for justice,” she said, “so they file their own lawsuits.”