The drought is very real. The places our water comes from are drying up, or polluted, or very expensive. This year’s Northern California snowpack was meager, and the federal government just declared its first-ever “water supply alert” for the Colorado River.

So this is a great time to review: Where exactly does Southern California’s water come from?

It’s the sort of question a child might ask while sitting in the bathtub, along the lines of why is the sky blue? It’s also a question I get from my editor, who is from Great Britain, where water is plentiful. And the truth is it’s something we all should be asking as we cope with the consequences of the climate emergency.

Even though it’s a super-simple question, it has a complex answer. Because we live in a dry place, it means we have to get our water wherever we can … with water that comes from a lot of different places.

We get our water from the sky, from hundreds of miles of aqueducts, from underground aquifers, and as it flows down from our mountains. We even recycle water from our toilets. Yeah. Ew. Not really, though. More on that later.

There’s also no one answer. The sources of your water depend on your local water provider. Most Southern Californians are drinking a blend of well water and water that comes from the Colorado River and Northern California.

Read on to understand more about the different kinds of water flowing from your faucet.

The Original Bigfoot: The DWP

To start, let’s look at the original Bigfoot water agency, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Examining the DWP’s role is critical to understanding the hubris the city has exercised in moving water around since the early 1900s. The movie "Chinatown" is just fiction, but it’s inspired by the real story, which has just as much intrigue.

Back when Los Angeles was really a nothing burg, William Mulholland was in charge of the water system that eventually became the DWP.

A self-educated civil engineer, he realized through his dealings with farmers and city leaders that the city couldn’t sustain its rapid growth without a substantial supply of water.

Farmers and ranchers up north had plenty of water, as snowmelt from the Eastern Sierra snowpack flowed into the Owens Valley. Mulholland figured, why not bring that water down to L.A. through a long aqueduct? He managed (through proxy buyers) to secure the water rights for L.A. and land along the aqueduct route.

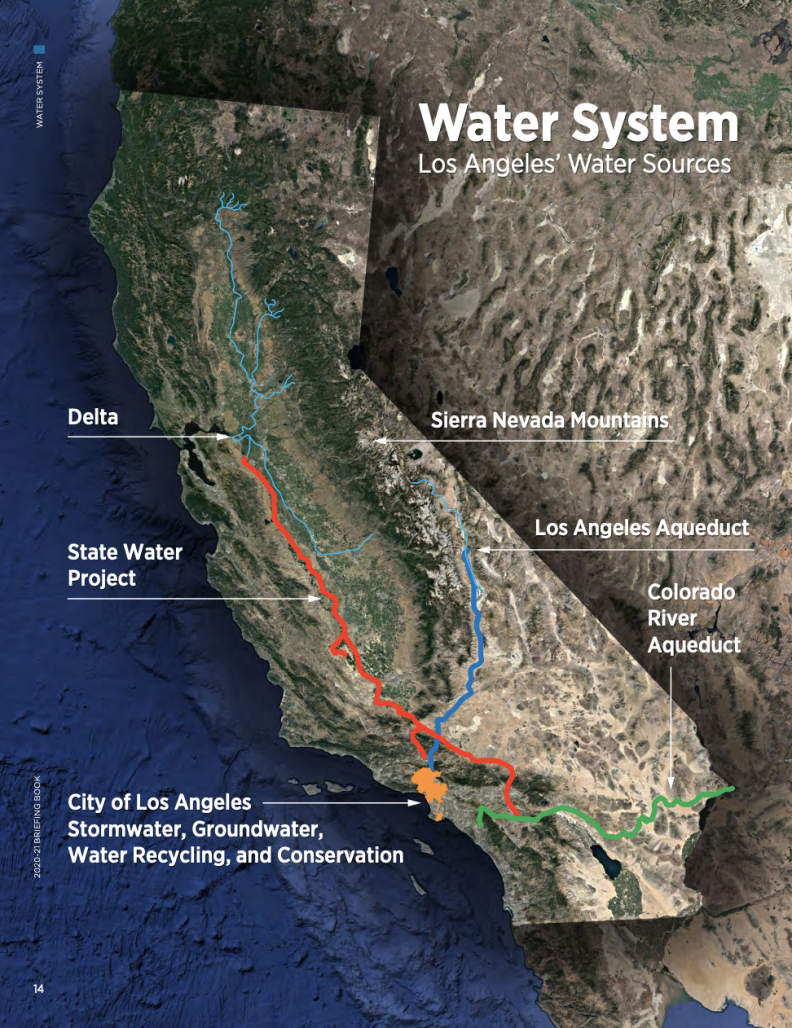

Mulholland oversaw the construction of the 233-mile Los Angeles Aqueduct that starts in the Owens Valley in the Eastern Sierra Nevada and ends just north of where the 210 Freeway intersects Interstate 5. Look up and to the right when you’re passing Balboa Blvd. heading north on the 5 to see the water cascading as it emerges from giant pipes and splashes along its final descent into L.A.

Much has been written about the political and legal battles stemming from that water rights grab. Eventually Los Angeles was made to share a good portion of the water with Owens Valley ranchers, and to reduce the health and environmental damage from dust flying off the dry Owens Lake bed, whose water source was diverted to L.A. The aqueduct also diverted water away from the Mono Basin and the LADWP has had to invest in environmental restoration projects there, as well. (If you really want to geek out on L.A.’s water, there’s more in the DWP 2020-21 Briefing Book,)

There are actually two aqueducts; the first was completed in 1913 and the second was finished on a parallel route in 1970. (See the video of our aerial tour.)

Water from L.A.’s aqueducts supplied about 48% of the city’s water needs over the past five years, DWP says. At one point, the agency had so much water from the large snowpack that the city was able to put some of it underground for future use.

But when droughts extend across several years — which is the situation developing right now — the snowpack is meager, and the aqueducts make up a smaller share of L.A.’s water supply.

That means that in dry years, L.A. must buy water from the wholesaler Metropolitan Water District. (See below for more info on that agency). That water is more expensive than the city aqueduct water, so in some years, DWP customers are billed a surcharge for the imported water.

Nowadays, DWP delivers some 435 million gallons of water a day to 735,600 customer connections, an annual total of 159 billion gallons. But it doesn’t all come from the same place.The city is so big that the mix of well water, aqueduct water and MWD-imported water is somewhat different for each area.

Mayor Eric Garcetti has declared that Los Angeles should wean itself from MWD-imported water. For one thing, MWD water is more expensive than L.A.’s aqueduct water. And it will continue to be, assuming L.A. pays part of the very large costs of a new water tunnel in Northern California. Also, the Colorado River is over-subscribed, that is to say, its water has been contractually promised to more agencies than the river can actually deliver. So most users end up taking less than their full allotment.

In the five years ending in 2020, about 89% of L.A.’s water came from aqueducts operated by MWD and DWP. The city is now aiming to reduce its use of aqueduct water to just 30% of its total. That means more water will have to come from local sources.

Groundwater: Fairly Pure, Except In Parts Of LA

Deep in our collective history, humans learned that if you dig or drill deep enough into the ground, you can get water. Groundwater tends to be fairly pure because it comes from rainfall that flows across the land and filters down through many layers of rock to reside in natural underground reservoirs called aquifers.

But this is L.A., a city that has a history of dirty industry that dumped or leaked dangerous chemicals onto the ground and those substances — like industrial solvents used in factories during and after World War II — polluted the aquifers in part of the San Fernando Valley. About half of the city’s active groundwater wells are closed because the water underground isn’t fit to drink without extensive treatment.

For Los Angeles to become water sufficient and use less imported water from the Colorado River and Northern California, it would have to take the costly step of removing contamination from the San Fernando Basin underground aquifers.

The plan for L.A. to become water sufficient also relies on conservation measures like people replacing their thirsty green lawns with drought-resistant plants (or, in my case, with front yard drip-irrigated vegetable gardens).

Toilet To Tap: No, It’s Not Icky

The plan also relies on big water recycling efforts, leading to L.A. recycling 100% of its wastewater by 2035, under Mayor Garcetti’s plan.

Right now, they take the sewage that flows from our showers, dishwashers, sinks and toilets, separate the solids from the liquids at places like the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant and process the heck out of it to make it safe to store in the ground or release into the ocean via a mile-long pipe.

But when the plant backs up, like it did in July 2021, it’s a big awful smelly mess.

To achieve the ambitious 2035 goal, DWP would partner with the L.A. City Sanitation and Environment Department to transform wastewater into drinkable water. We’re not there yet, but DWP has launched a pilot project that’s designed to eventually process water sufficiently that it can be combined directly with drinking water. That isn’t slated to happen until about 2028, just in time for the Olympics. Won’t the tourists be pleased to be part of this effort!

For now, treated recycled water at the Hyperion plant is sent to the Water Replenishment District of Southern California, which filters the water into underground aquifers where it becomes groundwater to be pumped out later.

We Need to Capture More Storm Runoff

Managing stormwater throughout Southern California’s watershed requires a regional system that includes Los Angeles County. The rain falls in the mountains and valleys and is channeled into rivers and flood control channels and, for the most part, efficiently out to the ocean.

A number of dams (like the San Gabriel Dam and the Morris Dam on the San Gabriel River in the pictures below) and concrete channels were constructed to tame natural streams and rivers during the 1900s after floods killed people and swept away homes.

Those dams and channels safeguarded the region from flooding and enabled the sprawling growth of Southern California, for better or worse.

But the system wastes water that could augment the local water supply for that large population.

L.A.’s plan to become self-sufficient calls for catching even more storm runoff. Once captured that water is directed underground where it filters through layers of porous soil and rocks to recharge aquifers. Ultimately, it’s pumped out by wells for our use.

An example of such a project are the water-filtering catacombs built underneath the ball fields at Sun Valley Park. The concrete structures relieve flooding in the Sun Valley area and get more water filtered into the ground.

There’s been a movement in recent years to return the L.A. River and San Gabriel River to a more natural state. In some places, the concrete channel bottoms have been broken up to allow water to seep into the ground and replenish underground aquifers.

In other places, channels divert the water to large open fields known as spreading grounds. Some of them, like the Dominguez Gap Wetlands shown below, double as scenic hiking spots.

Some efforts to capture stormwater will be paid for by proceeds from the L.A. County Measure W parcel tax on impermeable land, in other words, surfaces that prevent water from soaking into the ground. If you get a property tax bill, that’s one of the charges that appears on it. Homes and businesses throughout most of L.A. County pay 2.5 cents per square foot of concrete, roof, brick and even swimming pool surface they own. (Why swimming pools? The rainwater that falls into swimming pools cannot soak into the ground or be repurposed.)

By the way, the city has an entire system of open-air reservoirs that once were used for storing drinking water. However, it turns out the water combines with light and certain molecules to form cancer-causing chemicals. So, those open-air reservoirs had to be taken out of service. Now, some — like the Silver Lake and Hollywood reservoirs — are pretty to run or hike around, and they’re also used by firefighting helicopters to fill their tanks.

Because open-air reservoirs are a no-go, DWP built massive covered reservoirs to store water. One is up above the Hollywood Reservoir, and the other, still under construction, is visible from the 134 Freeway alongside Griffith Park. Those reservoirs, plus large earthquake-resistant pipes, make up for the lost water storage in open lake-type reservoirs.

The Big Kahuna: The Metropolitan Water District

A lot of the water we get comes from the Big Kahuna, the Mighty Met: the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. But you don’t buy your home or business water directly from MWD.

It’s considered a “wholesaler” of “imported water.” Its customers are 26 public water agencies that serve homes and businesses in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego and Ventura counties. About 19 million people drink water that has MWD water mixed into it.

The agency was formed back in 1928 to duplicate what Los Angeles did — build an aqueduct to bring water from a wet place to a dry place with a swift-growing population. In this case, it was an aqueduct to bring Colorado River water to Southern California.

It worked pretty well. The water started flowing in 1941. In the 1970s, the MWD extended its tentacles north, building the California Aqueduct, which gets water from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the freshwater place where the two rivers come together and eventually flow to the ocean.

The MWD’s California Aqueduct is problematic because of the location of the inlets in the delta that pull water into the aqueduct. The inlets collect so much fresh water from the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers that salt water from the ocean is intruding farther into the delta, creating problems for the area’s fish and wildlife.

A proposal to build new intake towers farther upriver that would feed fresh water into two giant tunnels to the aqueduct ran into strong opposition from Los Angeles and others. They balked at the $17 billion price tag of the Twin Tunnels project and it got cut back to one tunnel. It’s now a project dubbed the Delta Conveyance.

The Patchwork Of Water Retailers

There are 88 independently-governed cities in Los Angeles County plus large swaths of unincorporated area overseen by county government. Water in those areas is delivered by many, many different public and private water utilities.

The patchwork nature of the water systems is a relic from early days when somebody would dig a well to irrigate their crops. That private well might then provide water to homes, and it might become part of a private or public water system. And that happened dozens and dozens of times across Southern California.

As a result, there are some very small water systems that have failed to keep up with maintenance or modern water quality, and their customers suffer. That’s what happened with the Sativa Los Angeles County Water District serving parts of Compton. The water turned brown and the county stepped in to take it over.

As a consumer, you don’t have to accept poor water quality. California was the first state in the nation to declare that safe, clean, affordable and accessible water was a human right. You can contact your water provider (the phone and website should be on your water bill) if you suspect a problem in your water and/or contact the L.A. County Department of Public Health drinking water program.

How water districts are governed is also a patchwork.

- There are water districts operated by cities and counties

- There are special districts that have their own appointed or elected governing boards that answer to the public.

- There are private water companies

- There are water companies whose parent firms are traded on the stock market.

Most of those agencies, both public and private, serve up a combination of MWD-imported water and local groundwater. A very few even make use of recycled water.

The Long Beach Water Department serves nearly 500,000 people over 50 square miles. About half of its water is groundwater pumped by wells, 40% is imported MWD water and 10% is recycled. The department is overseen by an independent board of water commissioners, one of whom sits on the MWD board.

Long Beach’s recycled water is mostly used to recharge underground aquifers, to water parks and golf courses and for industrial uses like oil extraction. (The city makes a lot of money in royalties from local oil rigs.) The more recycled water the city can put underground, the more it can pump later and reduce its purchase of imported water.

At least two large for-profit water utility companies also sell water to homes and businesses.

Cal Am Water, aka California American Water is a subsidiary of American Water Works Company, Inc. The parent company is the largest publicly-traded water utility and wastewater treatment company in the U.S., according to its investor website. Its customer base is about 15 million people in 46 states.

Locally, Cal Am serves:

- Bradbury

- Duarte

- San Marino

And portions of:

- El Monte

- Irwindale

- Monrovia

- Rosemead

- San Gabriel

- Temple City

- Unincorporated L.A. County and the Baldwin Hills area.

In addition, the company recently was approved to acquire the East Pasadena Water Company. The water for those areas comes from local wells, augmented by MWD-imported water.

Golden State Water Co. serves more than 143,000 customers in 49 cities and unincorporated communities. The company operates a number of distinct water systems that it has acquired over the years and serves up water pumped from various groundwater wells, along with water from the MWD’s Colorado River and Northern California aqueducts. Its Culver City service area is the exception, using only MWD water, and no groundwater.

One of the goals of state water regulators is to reduce the number of small, understaffed and underperforming water retailers, consolidating them into larger public or private companies that have more capacity to maintain and update water systems. So it’s likely that Golden State and Cal Am Water will continue to acquire more small water systems.

With Southern California and the far-flung places it gets its water going deeper into another multi-year drought it seems certain that our water will be more expensive as we collectively invest in new systems to clean and use polluted groundwater, to sanitize waste water and to build projects to capture, store and reuse rainwater. Those efforts could also include construction of plants to remove salt from seawater.

But at the end of that expensive ramp-up, it will be a success if Southern California is able to rely more on local water rather than supplies shipped in from afar.