Danielle Cordova and her daughter Alena are from a car family. They come from generations of lowrider and sports car enthusiasts and skilled mechanics. When 14-year-old Alena is old enough for her own ride, Danielle said one will be waiting for her.

“It's kind of like a tradition,” Danielle said. “Even my husband—her dad—he has the car from his dad.”

I met them at the Petersen Automotive Museum in the mid-Wilshire area of L.A. Despite her family’s self-described old school preferences, Alena was checking out an exhibit about the new school: electric vehicles.

“I heard that in California they're planning to start only selling electric vehicles,” she said. “So I kind of want to see how that goes because I could see it hitting California and then spreading all over America.”

Alena’s right; California passed regulations this year to end the sale of new gas-powered cars by 2035 — though 20% of new vehicles sold in 2035 can still be plug-in hybrids, which use both gasoline and electricity. And the ban only applies to new vehicles, so you'll still be able to buy a used gas car or keep your own, of course.

Given the state’s share of the auto market, the regulation is expected to spur electric vehicle sales across the nation. And the Biden Administration's new climate and tax law will likely further push EVs into the mainstream.

People are hungry for affordable options. According to a recent consumer survey from AAA, 1 in 4 Americans say they want to buy electric for their next car … mostly because of gas prices.

Pending global crises and supply chain issues, we’ll probably see more EVs on the road in just the next few years. Part of California’s mandate requires tripling the number of electric and hybrid vehicles sold by 2026. Affordability is likely to remain a big problem in the near future, but the California Air Resources Board (CARB) estimates EV prices will be on par with or cheaper than gas cars by 2030.

A Breath For Climate… And Health

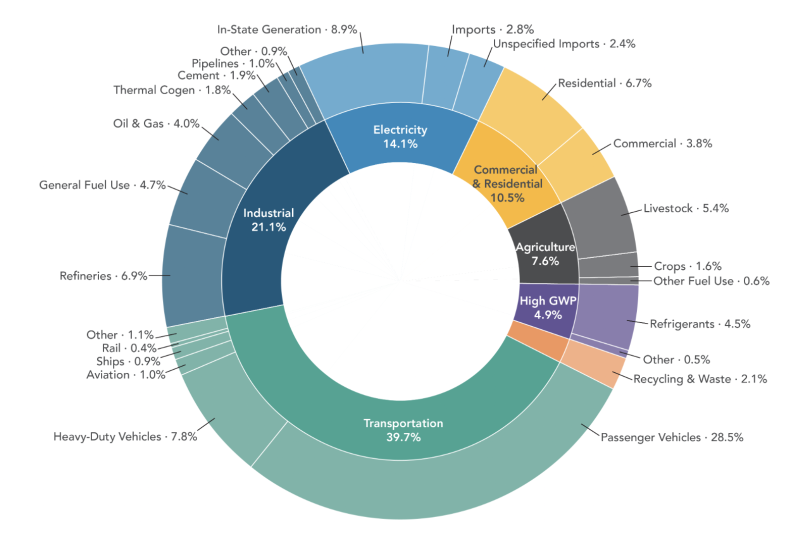

More than 40% of California’s greenhouse gas emissions are spewed from the tailpipes of heavy-duty trucks and millions of passenger cars, with the rest coming from vehicles such as trains and planes.

Globally, transportation emissions account for about a fifth of the carbon dioxide heating up the planet—and they further fuel our reliance on fossil fuels: data from the International Energy Agency shows that about 48% of global oil extraction powers one form or another of motorized road transport.

UCLA urban planning professor Adam Millard-Ball said that’s why getting more people into electric vehicles are needed to lower California’s—and the world's—greenhouse gas emissions.

We're not going to be able to resolve the climate crisis without electric vehicles.

“We're not going to be able to resolve the climate crisis without electric vehicles,” said Millard-Ball. “And that's mainly because transportation is such a big part of the climate problem.”

Gas and diesel-guzzling cars, buses and trucks are also the biggest source of L.A.’s infamous smog. If by 2035 all these state and nationwide EV goals do come to fruition, the American Lung Association estimates that the reduction in smog pollution would help avoid 110,000 premature deaths by 2050.

The Once-Promising History Of The Electric Car

In the 1890s, growing American cities were overrun with traffic and pollution, largely because of horses, the primary mode of transportation. And the manure was literally piling up. New York health officials estimated emissions from manure were killing tens of thousands of people every year.

A new technology emerged that might solve the problem: horseless carriages... or, as we call them today, cars.

To learn more, I met with the Petersen Automotive Museum’s chief historian Leslie Kendall. We walked through one of their current exhibits about the history of electric vehicles. The first one was developed by a Scottish inventor in about 1839.

We stopped in front of an old green car that looks essentially like a horse-drawn carriage without the horse. The 1908 Columbia Electric was one of 20 electric car models the company came out with.

“It exemplifies what the genteel motorist of the day would drive because they were very expensive,” said Kendall.

Yep, electric vehicles were way too expensive back in the day, too—about three times as much as the world’s first mass-produced vehicle, the Model T Ford, which also came out in 1908.

Electric cars then were powered by rechargeable lead acid or nickel cadmium batteries and, for those who could afford them, they were preferable to gas-powered options: At the turn of the 20th century, electric-powered cars were being bought in more numbers than their steam- and petroleum-powered competitors, Kendall said.

The Model T, for example, was loud, belched smelly fumes and you had to crank it up to get it going. But electric cars…you just stepped in, pulled a lever and hit the road. They were quiet and smooth, which made them especially popular with affluent women of the time, Kendall said.

We walk over to another car—it’s a little bigger, a little sleeker and it has windows and lush velvet seating: a 1915 Detroit Electric.

“Probably the most popular electric car,” Kendall said. “They made these until 1938, 1939.”

It had a top speed of 20 mph and an 80-mile range on a single charge. Thomas Edison drove one with a rechargeable nickel-iron battery he invented himself. But they, too, were were only affordable for the wealthiest in society.

“What the public was waiting for was for electric cars to become convenient… which also involves making it affordable,” Kendall said. “They had a lot of really good points, a lot of really favorable aspects. But, gasoline, it was cheap at first.”

The real game-changer, Kendall said, came in 1912 when Cadillac introduced a gasoline-powered self-starter.

“All of a sudden, gasoline-fueled cars just took off like crazy,” Kendall said. “Electric cars took a dive in popularity. Gasoline cars got more reliable, they got quieter, they got more powerful...They got to where they are today.”

Kendall said there wasn’t money in electric vehicles and, besides a few tinkerers, automakers largely stopped building them.

The boom in the gas-powered automobile dramatically changed culture and our cities. Los Angeles widened streets to make room for more cars and parking spots. There was plenty of oil here to support the auto boom. And freeways were prioritized over mass transit.

What Can The Past Tell Us About The EV's Future?

With thanks to cars, we don’t have to deal with mounds of horse manure in the streets anymore. And we can go a lot further, a lot faster—when there isn’t traffic, of course.

But when gas won over electric, it drove us into another corner: a climate crisis. And the fundamental issues the car was supposed to solve—traffic, air pollution, safety—have only become more firmly entrenched.

As Mark Twain famously said, “History never repeats itself…but it does often rhyme.”

It wasn’t until the 1960s that air pollution and oil spills spurred interest in electric cars again. And only in the last decade has the technology, such as lithium batteries, caught up to speed.

But we may not be learning from the past, said UCLA's Millard-Ball.

“We're so car-centric in L.A. and one thing that I think is a danger of the push for electric vehicles is we can then neglect sight of the other things we can do to not just reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also improve safety on the streets and reduce air pollution.”

He pointed to the 1970s, when L.A. was choked by smog much worse than we have today. Automobiles were a major source of the pollutants causing poor air quality around the country. But policy and technology helped: In 1970, Congress passed the Clean Air Act, one of the nation’s most significant environmental laws. Since then, despite massive growth in population and more cars on the road, the legislation has helped reduce air pollution across the nation by more than 70 percent.

The Clean Air Act also spurred new technology: it required new cars to have catalytic converters, which significantly curbed tailpipe emissions. But the other way to address pollution—encouraging alternatives to cars—fell to the wayside.

“There were those great promises that, OK, we're going to fix this problem partly through cleaner cars and catalytic converters," said Millard-Ball, "but also through getting people out of cars where they can—more people walking and biking and better buses.”

“In practice, the first part of that was incredibly successful. Air quality is still bad, but it's an order of magnitude better than it was in L.A. in the 1970s. But we didn't really take advantage of the second part in terms of building a transit system that is a real competitor to the private car. And I worry that the same thing is going to happen with electric cars.”

L.A. already has the most electric vehicle drivers and chargers in the world and has ambitious plans to expand that infrastructure.

If there needs to be trucks and cars, let's make them electric. But that should not come at the expense of actually doing the harder work of rethinking the way we use our streets.

The city has slowly added more bus and bike lanes, but has fallen far behind on implementing its own transit and mobility plan.

And, as LAist's Ryan Fonseca has reported on extensively, cars killing pedestrians has only become a bigger problem—and heavier electric cars (the new electric Ford F-150, for example, is about 1,500 pounds heavier than its gas-powered counterpart)—certainly won’t fix that or help with the potholes that plague L.A. streets, said Michael Schneider, founder of local mobility advocacy group Streets For All.

“If there needs to be trucks and cars, let's make them electric,” Schneider said. “But that should not come at the expense of actually doing the harder work of rethinking the way we use our streets.”

-

It's gonna be Yankees v the Boys in Blue

-

What candidates can — and can't — say they do

-

Nonprofit's launching fundraiser to keep it afloat

Schneider pointed to Santa Monica as an example of a city that’s doing transit right. The city has invested heavily in protected bike lanes, putting in bus-only lanes, and removing parking spaces.

But L.A. is moving slower. A recent analysis by L.A. Metro found that the agency could significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions through its investments in sustainable mobility and rapid transit, but that those reductions would be negated by the agency’s current plans to expand freeways.

And given the environmental and human rights impacts of mining for the rare earth metals needed for electric vehicle manufacturing, Schneider worries electric vehicles will only push us into another corner of consequence... as gas-powered cars did a century ago.

Science may show electric vehicles are an essential piece of the puzzle to address the climate crisis and improve air quality, but what’s also critical, said Schneider, is bigger investments in sustainable transportation options that don’t involve the automobile… even electric ones.