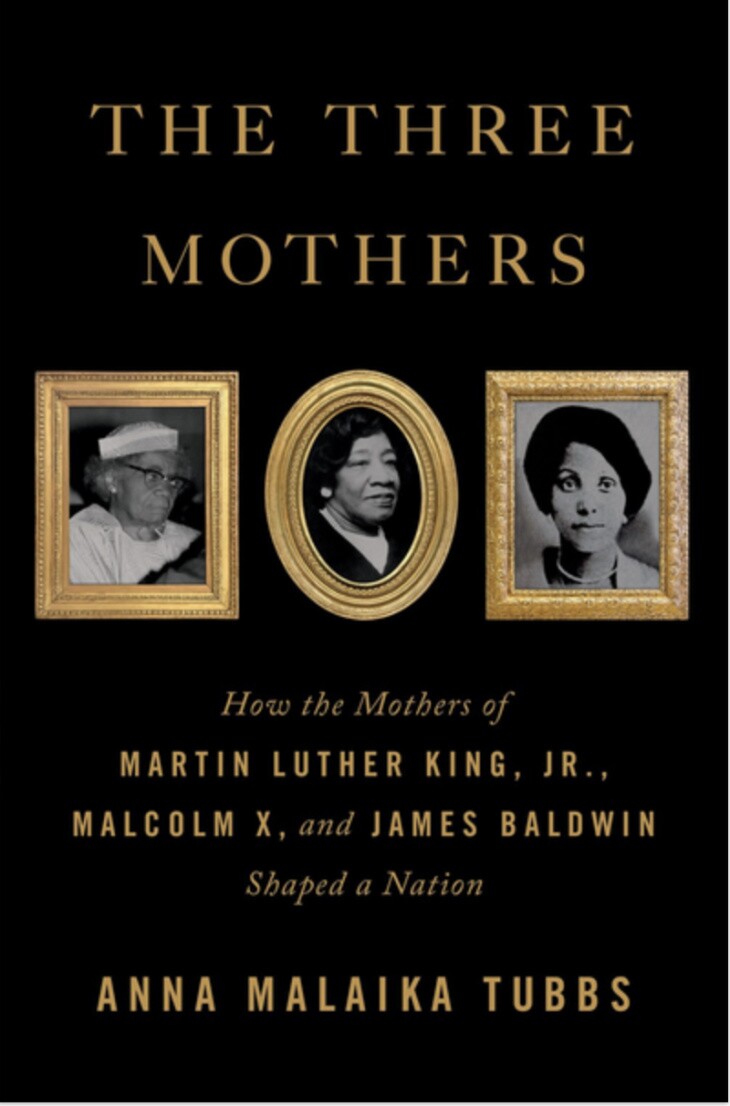

Black feminist scholar Anna Malaika Tubbs was inspired to write to "The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr, Malcolm X and James Baldwin Shaped A Nation" so she could explore the civil rights movement by looking at it through "the woman before the man." We talked to her about the experience of writing the book and how she has changed since she became a mother.

A Call To Advocacy

Q: When you think back to some of the people who have inspired how you see the world, who comes to mind?

My parents, in their very different ways, influenced my journey, including writing this book. My mom advocated for women's and children's rights everywhere that we went. She taught at different universities abroad. She is trained in international law, and she wanted to talk about those that had been forgotten, those that were being oppressed and those that we're fighting their own battles for freedom. She very specifically spoke about the importance of supporting women in order to support the community. She always said that if women are doing well in a community, then that community will do well, and if they are not, if they are being ignored, then that community will continue to struggle with whatever issue it is that they are facing.

-

We're highlighting the contributions of Black Angelenos — in activism, music and art, sports, literature and more. This coverage is part of The 8 Percent, an extension of LAist's Race In LA which explores the inextricable ties between L.A. and its Black residents.

-

These people are making meaningful contributions but not necessarily in the limelight. They may attract a level of celebrity in their communities and among their neighbors but they're not famous in a Hollywood sense. Nonetheless, we're taking time to amplify the notoriety of these changemakers. They're sharing the stories of what they've done and for whom — unfiltered and in their own words.

Q: What does being an advocate mean to you?

Being an advocate means not only standing for somebody but standing and learning about experiences for yourself. It's saying, 'I'm gonna learn about this for myself, and I'm also going to consider what has already been done,' instead of just jumping in and thinking from the beginning you know what's best for that cause or that person simply because you have a degree. That was something that my mom always did very well, she would spend time just getting to know people before she proposed anything and she went to places that we're facing crisis -- she worked in Iraq, Afghanistan, in South Sudan -- because she wanted to know these places for herself and she wanted to meet the people [for herself].

Writing 'The Three Mothers'

Q: What inspired you to write "The Three Mothers"?

When I started my Ph.D, all I knew was that I wanted to join other scholars who were correcting the erasure of black women's stories. I was really inspired by Margot Lee Shetterly's "Hidden Figures." I was also inspired by Isabel Wilkerson's "The Warmth of Other Suns." Both books speak to the importance of understanding the Black American experience in order to understand the American experience, in not only our history but where we find ourselves as a country today.

Q: Why did you decide to explore the civil rights movement through the lens of these three mothers' lives?

One area where we often speak about men as being leaders and celebrate men as leaders is the civil rights movement. I got really excited about the notion of the woman before the man. Before the man is even thought of, even conceived -- [the concept of] motherhood just stuck with me. I looked into several different men of the civil rights movement and their mothers before I came to the women that I study in the book: Alberta King, Berdis Baldwin and Louise Little. I chose them for several reasons. Their lives were just incredibly interesting from even the little I could find at the beginning. They were all born within six years of each other and their famous sons were all born within five years of each other. They represent the diversity in the nuance of the Black experience.

Fighting For Women

Q: You've been an outspoken advocate for gender justice. In your role as First Partner of Stockton, you pioneered the release of the original Report on the Status of Women in Stockton in 2018. You also hired the city's first Gender Justice Officer. Talk to me about your role in that process and its legacy in the city of Stockton.

When my partner was the mayor of Stockton, and, even when he was running his campaign, I was by his side. We would go to all these debates and after each one we would talk about what went well and what could be improved. After each one, though, I was shocked that nobody was talking about gender, nobody was asking him or any of the other candidates what they were willing to do for women or what they were going to do to change the status of how women were doing in our community. I said to him, 'This is wrong. You are going to miss a huge piece of the puzzle if you don't have data, or if you don't focus on the issues that are specifically affecting women here.' To his credit, he said, 'You're right. You know more about this than I do. How do we start that?' And that's when I said let's start with getting numbers behind it.

Q: Why a report? Why tackle an issue many might say demands on-the-ground action by looking first to statistics?

So often women, especially women of color, who have been marginalized can say very clearly what issues they need help with, what they need support with, what policies need to change. But many [critics] will say, 'Oh you're exaggerating that.' There's this notion that you're being emotional. However, when and if there's a number behind it, if there's research behind it, we can say, 'Look at this data. Look how [women in Stockton] compare to women in the rest of the state, in the rest of the country, etc.' So we did this report to bring attention very specifically to the women in Stockton.

Q: What is one thing that resulted from that report you feel most proud of?

[We found that] one-third of households in Stockton with children under age 18 were helmed by single mothers. If we weren't coming up with policies that would help single mothers specifically -- maybe having some kind of child care pilot program or the universal basic income pilot program, that my husband has become well-known for -- we would not understand why there were gaps not being filled. So women, and specifically women of color, and single mothers started to become more of a focus of his work after the report.

RELATED:

- As Awards Season Begins, #OscarsSoWhite Creator Reflects On Legacy Of Viral Movement To Diversify Hollywood

- Everybody Loves The Sunshine: Black Angelenos Helped Shape The City - Don't Erase Us

- I Turned To Art To Be A Better Ally To The Black Community

Q: You mentioned earlier that you felt called to address the erasure of Black women's stories.

As a Black woman yourself, what was it like journeying through the lives of these women and working to put the pieces together about who they were as individuals?

Journeying through their lives was so powerful, and it's something that I'll carry with me for the rest of my life. I became frustrated that that people didn't already know these details about their lives. It's really shocking because of the very obvious and direct connections to their sons' works. Why didn't we already know this? Why were they being erased? Why were they being forgotten when they were clearly so important? That was really difficult for me, but I also felt honored that I was going to change that, and I was gonna share their names with the world as they should've already been.

Personal Growth As A New Mother

Q: In exploring the lives of "The Three Mothers" what did you learn about yourself?

I became a mother while writing this book. I started the research beforehand, but my second year into the research I found myself expecting my son. [My pregnancy] gave me a new layer of connection to [the mothers] because as much as I was overjoyed and excited, the fact of the matter is that it's very dangerous as a Black woman to have a child in the U.S. We are more likely to die in pregnancy and childbirth, whether or not we're educated, whether or not we have access to different resources and connections.

The American gynecological system is built on this notion that Black women are less than human, that they don't feel pain in the same way that other people do. It was literally built by experimenting on the bodies of enslaved women. We see remnants of that today when Black women say something is wrong, and they're not heard and many die as a result of that. I was terrified, but studying these women gave me hope and some feeling of power and agency. [I felt like] there were things I could do to be a part of changing the system and transforming it. I realize that Alberta, Berdis and Louise also knew tha, like themselves, their children were going to be seen as less than human. Instead of accepting that as something inevitable, they became part of the change. There is something very politicizing about Black motherhood because this is your most precious being, and you need to help the world see them in the same way that you do.

Q: What is the biggest lesson you have taken away from the process of writing "The Three Mothers"?

Writing this book taught me how powerful and influential and important my life is. And, I want more Black women to view themselves that way. It's not that we are allowing ourselves to be erased, because there's so many different factors that are playing a role in our erasure, but there is something that we can do about it. We need to share our stories. We need to be willing to take credit for our own contributions and kind of stand and say, 'I am here, and I deserve recognition.'

(Left) Berdis Baldwin holds her infant son; writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin poses at his home in southern France, 1979. (Baldwin family archive; Ralph Gatti/AFP via Getty Images)

Q: Who did you write this book for, and what do you hope people who read it will take away?

This book is for everyone; there's something that everyone can gain from it. I hope that if you are a Black woman you feel celebrated and if you're not that you learn about us and our experiences and celebrate that. This is a time where more people are realizing that they need to learn more about us and how we've made it through. They're understanding that they need to do everything they can to make life easier for Black women in the U.S. today. But when I think about the three audiences that I carried with me in my heart as I was writing this book, first, 100% it's for Black women. This is a love letter to my community to celebrate us and our many different ways of living, loving and believing. Secondly, this is a celebration of motherhood. In so many ways, mothers are under appreciated, forgotten. Our contributions are taken for granted, and I wanted to change that. I want us to see the role of motherhood as powerful, influential, strong. Thirdly, it's for activists. I thought about activists a lot while writing this and celebrating the communities that raised us to be the fighters and the activists we are.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.