On the inside of my home, I'm Puerto Rican. The first American-born generation on my mom's side, and the second on my dad's side, practicing the customs and traditions of my Puerto Rican heritage. Watching Spanish television programming and listening to Spanish radio stations, as well as American English television and radio.

-

From June 2020 to July 2021, we published your stories each week to continue important conversations about race/ethnicity, identity and how both affect our lived experiences. We now have a new series Being American, which is again soliciting your essays.

-

Read:

On the outside, especially having grown up mostly in Los Angeles, in Latin American neighborhoods like Koreatown in the inner city, I am Black.

At least, I have come to the realization that this is how most people view me. The split identity that others project onto me is something that until recent years, I have been at odds with.

Many older Latinos recognize me right away, and immediately speak to me in Spanish. I can't tell you how much this warms my heart. But many of the younger generation, or even my own generation, don't get it.

Here is my Afro Latina L.A. story.

'LOS BORICUAS'

From as early as I can remember, family, food and music were the center of my life.

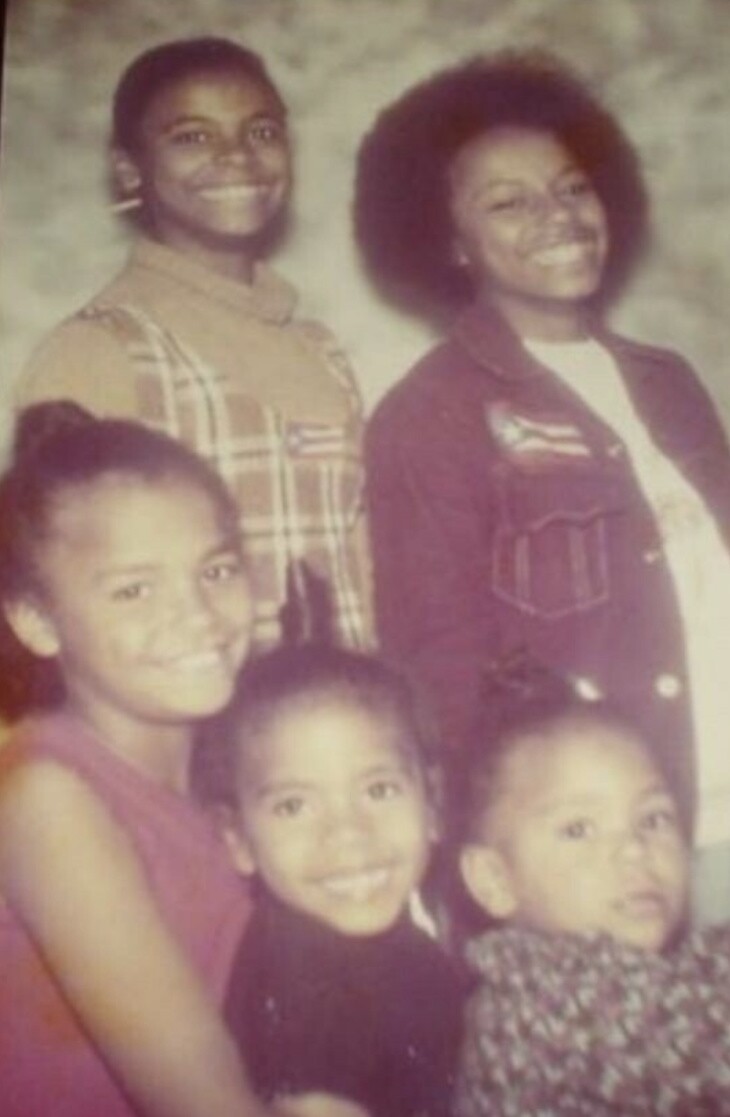

My father always emphasized what it meant to be Puerto Rican. He fostered a strong sense of pride within us. Back in the 1970s, it was popular to wear patches on your clothing, even if you weren't patching a hole.

We had Puerto Rican flag patches on our jean jackets, our overalls, our shirts, we had them everywhere.

We were very fortunate in the 1970s to be a part of a very strong Puerto Rican community in the San Fernando Valley. We were a multi-family, cohesive community, bonded not by blood but by traditions and culture and lots of love.

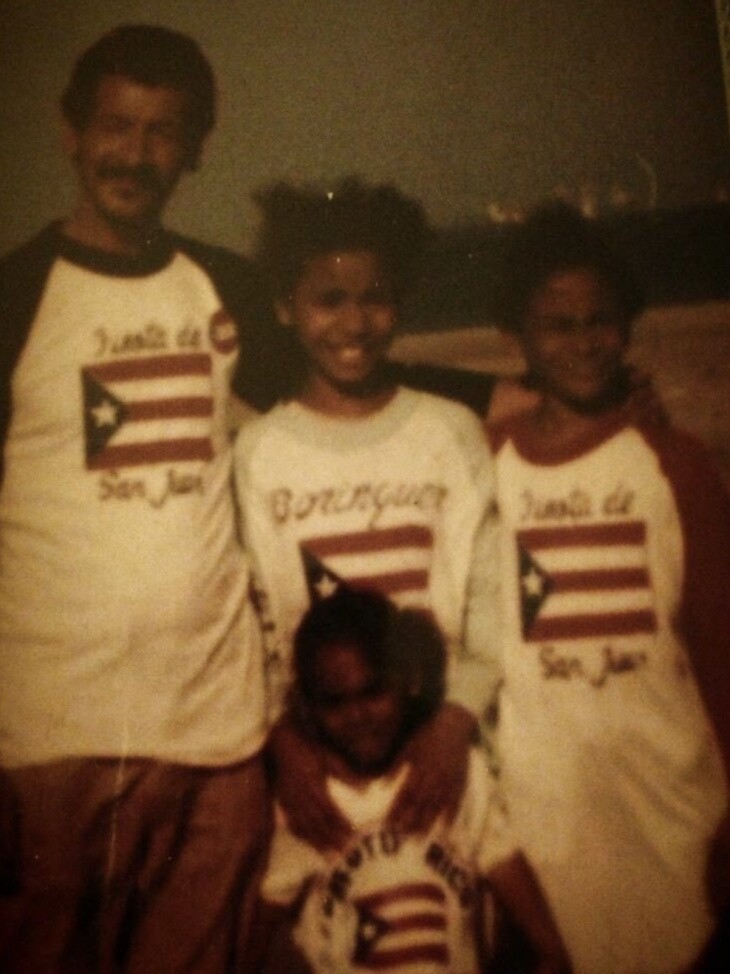

We had our very own baseball team, called "Los Boricuas." We all gathered at the parks on the weekends, playing handball, cooking, eating, and playing dominoes.

We were the Romeros, and we were joined by the Sotos, the Rioses, the Robleses, the Colones, the Maldonados, the Gonzalezes, the Montañezes, the Vegas, the Roldans, the Rosarios, the Estradas, and more families that I don't remember right now. We were like family, many of us inter-marrying later in life. Everyone was a cousin, an aunt or an uncle.

Everyone at school and in our neighborhood knew that we were Puerto Rican, unlike most of our neighbors. We lived on the border of Arleta and Pacoima.

This was probably the beginning of white flight from the San Fernando Valley, because I do remember that most of our friends in the neighborhood were either Chicano or white. Except for our new neighbors across the street, who were from Jordan. Our neighbors to the left were white, later replaced by a newly immigrated Mexican family when they moved away.

We lived on a quarter-acre lot on a dead-end street. Our home was where everyone gathered for backyard parrandas. There were congas being played, food being cooked, people drinking and having a good time. We were happy.

We children all played together, and we looked forward to large multi-family gatherings. We all went camping, boating, and fishing together to the Colorado River, Kern River, Hansen Dam, Castaic Lake, Lake Piru, Big Tujunga, Bishop, Mammoth.

We would caravan all over Southern and Central California. There were a lucky few non-Puerto Rican families who joined us, among them were the Ortegas and the Avaloses, who were Mexican, the Trallers and the Mendelsohns who were white, and the Stewards, who were black. (Side note, Bill Steward later became my stepfather.)

That all ended abruptly with my parents' separation in 1978, when I moved to Koreatown with my mom.

IN THE CITY

My grandparents moved 3,000 miles from New York to live next door to us and help my mother take care of her two youngest children, myself and my little sister, Cristina. My Titi Yiya (pronounced "Jiya," although my aunt's real name is Iraida) also moved to Los Angeles and lived a few doors down from us. Two of the Maldonados, our old neighbors, also followed.

In that respect, I still had a strong Puerto Rican influence in my life. To this day, my ethnicity influences my household traditions and my diet. It influences how I view the world.

But growing up as a proud, multiracial Puerto Rican in the Latin American neighborhoods of central Los Angeles had its challenges.

It all goes back to the existence of African slavery in Latin American countries. To this day, many people from places once colonized by Spain try to deny the existence of African ancestry in their own country. It is a little-known fact that there are African descendants throughout the Americas, including in Mexico, Guatemala, Argentina, Chile, Peru, and so forth. Countries whose citizens vehemently deny this fact.

They adopted the ideology of racism against Black people because they were colonized by the same Europeans that colonized what is now the United States. In Latin America, as elsewhere that European roots are valued, it is easier to deny your Blackness than it is to deal with the reason behind your shame. It is also easier to place yourself in what you see as a higher ranking if you believe another person to be beneath you.

There is a color hierarchy in the Caribbean, if you will. But there is also a clear understanding of our region's African past and it is deeply embedded in our culture, no matter our skin color. In the Carribean, we celebrate our African ancestry.

We recognize that it is a deep rooted, respected part of our heritage. It is in our food, our music, our art, our spirituality, our dance and in all aspects of our culture. Without the African part of our ancestors, we do not exist.

There were few, if any, Caribbean residents in the mostly Latino immigrant neighborhood in Koreatown that we moved to when I was in the 4th grade.

I had to justify my culture to people who laughed at my hair or my skin color. The girls called me "ugly" and implied that no boy would be attracted to me. I had to prove myself as a Latina. Prove that I spoke Spanish. I never had to do that when we lived in the San Fernando Valley.

Once I proved that I was Hispanic they accepted me into their ranks. Most of the bullying stopped. That made me extremely uncomfortable -- especially after the same kids had just finished calling me the N-word.

This led to a lot of fist fights. Deep down inside, I didn't feel comfortable knowing what they'd really felt about me before they knew my story. It was very hurtful.

One well-meaning friend would say, "She's not a 'n_____,' she's Puerto Rican!" As if that somehow improved my station. As a fellow Puerto Rican, the only one of three in the elementary school we attended in Koreatown, was she not also multi-racial? Yes. The answer is yes, but she is much lighter skinned than me. So does being a lighter-skinned Latino/a automatically absolve you of any Blackness? Are you now white-passing? No. The answer is no.

The neighborhood I lived in before my parents separated felt different. I fit in there. I remembered it as a place where Puerto Rican, Jordanian, Mexican, Black and white Americans all lived in harmony. Whether or not I was different, I never felt that way.

MORE FROM OUR RACE IN LA SERIES

- As A Black Nurse At The Pandemic's Frontlines, I've Had A Close Look At America's Racial Divisions

- 'What Are You?' 'Are You Adopted?' A Biracial Black Woman Gets Real About The Questions People Have The Nerve To Ask

- Reading While Black, And Other Ways To Court Trouble

- Reparations And Reinvestment: Contemplating The Proverbial '40 Acres And A Mule' Today

- Claiming My Dignity On A San Fernando Valley Street

- The Day My Brother Learned To Fly

- In The Process Of Becoming American: A Proud Son Of Immigrants Reflects On His Family's Past And Future

- 'Black Enough?' Mixed Musings On My Skin Color, Hair, and Heritage

- Please Do Not Call Me A 'Mutt' (Not Even You, Mom)

- Connecting Family Stories: A Latina Angeleña Explores Her Deep California Roots

- From 'Go Back To Your Country' To A Vice President-Elect Who Shares My Grandmother's Name

- My Mom Was A Black Entrepreneur. I Never Thought About It, Until Now

- How To Participate In Our Series

What's more, I am a product of busing. I was bused from the inner city for half of my 4th grade year to Dixie Canyon Avenue Elementary in Sherman Oaks, and half of my 7th grade year to a gifted magnet, Alfred B. Nobel Jr. High School in Northridge, both in affluent, mostly white communities.

This, too, helped to shape my reality, and how I viewed the world. As in Koreatown, here I was also an outsider.

It was during this time that I met kids who were bused in from Black communities. As an Afro Latina, and I'd had little to no experience with these new peers, other than a few Black friends in Koreatown who just accepted me. So when these new girls admired my hair and asked me what I was mixed with, I would answer, "I am not mixed, I am 100% Puerto Rican."

My 12-year-old self didn't know that I was "mixed." All I knew was that I was Puerto Rican. My new schoolmates did not understand or approve of my response. This led them to say things like,"You just want to be white." Calling me "white" led to more fist fights.

It seemed like I had to fight every ethnic group to defend my identity.

Well, not every group -- but that had other problems. I'll note that the question of race or heritage never came up around my Asian and Caucasian schoolmates. Not because they were nicer or better, but because they automatically assumed I was Black, and never called me names.

It was a silent assumption, which is even more insidious than the curiosity and disdain of the former.

'WHITE' PRIVILEGE

It wasn't until a decade later that I learned to tell people that I was a mix of three races: African, European and Indigenous. People are comfortable with this because it makes more sense to them than just being Puerto Rican alone. They don't call me names, they just smile in acceptance.

Because what is a Puerto Rican? We are a mix of mainly three beautiful races. It is a logical explanation that people can understand and it doesn't create any hostility toward me, in most cases.

After experiencing the hostility that I went through beginning in 4th grade, I grew up thinking that white people were much nicer and less racist, because the ones that surrounded our family back in the Valley were all love, and nothing racist.

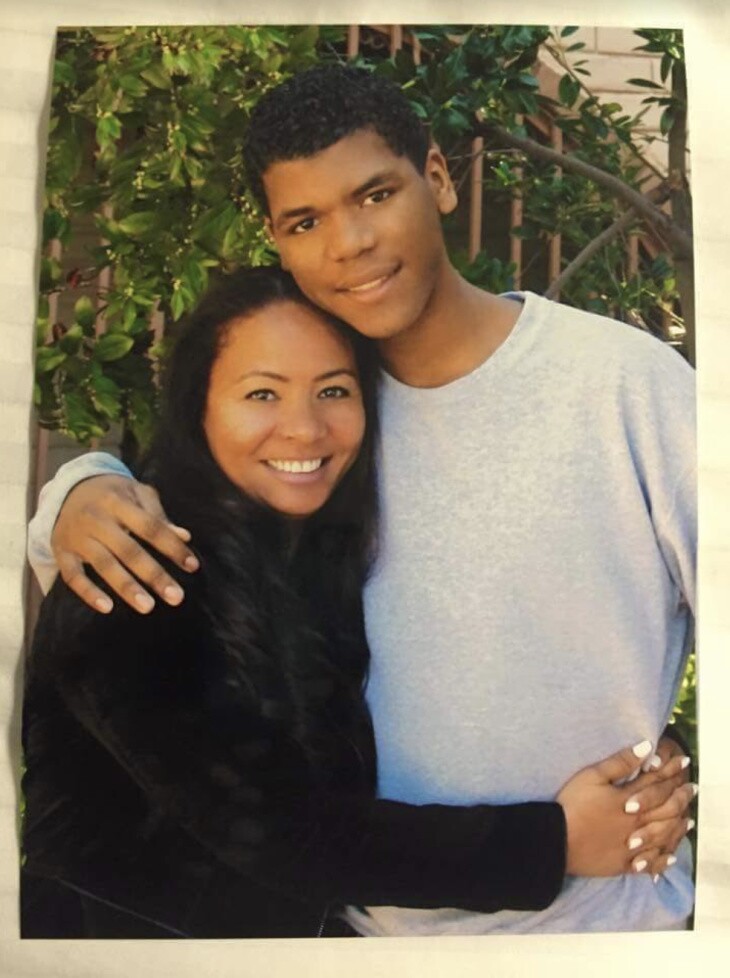

It wasn't until I had my son, who is half Jamaican, that I realized that nothing could be further from the truth. My son is much darker than I am, and 6' 3" tall.

Let's just say that the world has not been kind to him.

We moved to the Santa Clarita Valley 20 years ago, when my son was only three years old. I wanted to raise him in a good public school and a safe community, like the one I lived in when my parents were still together.

Little did I know that although the Saugus Union School District was in the top one-fifth of school districts in the state of California, its Black students were performing at the very bottom of its ranks, as I learned from School Accountability Reports. I learned that the school districts in the Santa Clarita Valley were failing their Black and Latino students.

I saw adults charged with educating and counseling our children treat my son in a discriminatory fashion, which was injurious to him and affects him still to this day.

This has deeply affected my views and opened up my eyes to a new level of ignorance and intolerance in the suburbs that I was blind to before. My son calls that my "white" privilege.

I am neither white, nor white-passing. But I have grown up with a certain privilege as an obviously multiracial person, and that is not always available to my son as a Black male.

IN LA, 'LOVE THY NEIGHBOR'

It has taken me decades to assimilate into the American culture of Los Angeles in a way that feels comfortable to me, without feeling at odds with everyone.

Today, I am comfortable no matter where I go or who is around. One day, I will tell you a story about my experiences visiting Puerto Rico, and how being born in New York City and raised in Los Angeles all but eliminates my heritage as far as they're concerned on the island. It's laughable, actually, because I am a foreigner there.

Growing up in a diverse city such as Los Angeles has afforded me a look into many different cultures and nationalities. I love and respect African Americans and their very rich culture. I love my Latino brothers and sisters regardless of their color. I love Asian American people of all national origins. I love all of their food and respect their cultures. As I do love my white American and my European friends. (Shout-out to my two French friends who I love so much).

I have been eating sushi, bulgogi, stuffed grape leaves and tacos since before the age of 10. This is what L.A. does, and L.A. is home.

We're all one race, the human race. "Out of many, one people," as they say in Jamaica. Love thy neighbor. We're only on this planet for a brief time and we only have one life to live. If we love our brother as we love ourselves we will be fine. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Nadine Romero was born in the Bronx, New York in 1969. Her family moved to Southern California in 1972. She works as a commercial insurance broker and makes her home in the Santa Clarita Valley. Nadine is a self-described "quirky 51-year-old" who loves to dress up in full costume to go to Renaissance Festivals and has driven solo across the United States -- both ways. Along with skiing, hiking, roller skating, traveling to different countries and making handmade soaps, her favorite thing to do is spending time with her son Gavin, 23, and her Australian Cattle Dog, Freyja.