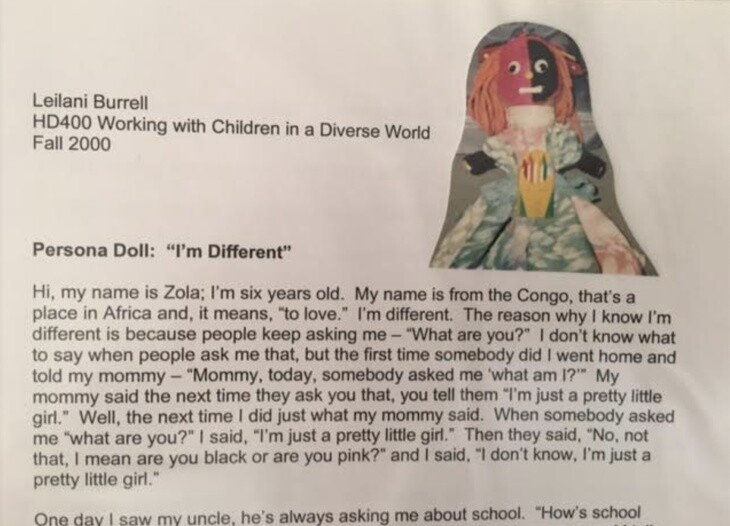

When I was a student at Pacific Oaks College in Pasadena more than 20 years ago, studying for my undergraduate degree in human development, I was assigned to create a "persona doll."

-

From June 2020 to July 2021, we published your stories each week to continue important conversations about race/ethnicity, identity and how both affect our lived experiences. We now have a new series Being American, which is again soliciting your essays.

-

Read:

A persona doll is a creative and often therapeutic way to tell a story. Using the persona doll allows the storyteller to convey the story in a non-threatening, non-invasive and safe way. The story that is being told is the doll's story.

There are many ways to create a persona doll. You can create a doll and then tell the doll's story, or you may have a story in mind that you want to tell and then create the doll. The story always belongs to the persona doll, not the person who wrote or told the story.

Persona dolls are very useful in therapeutic settings, especially when working with children, as I frequently do. However, I have found that persona dolls are helpful for all ages and genders. We all have stories we want and need to tell.

"Zola" was my persona doll I created during the college class I attended, in which the students were asked to consider how our lives were shaped, during our early development, by the social and political context of the time. We then wrote our persona dolls' stories.

Zola's story was drawn from the early experiences of a young girl growing up during the early 1960s, as I did. The young girl living those experiences was me. Zola's mother is white and her father is Black, just like my mother and father.

Zola is a young child whose only concern is to play. But people keep pointing out to Zola that she is different, and Zola can't understand why.

I wrote her story in her voice and from her perspective, in the language of that era.

Zola's story has stayed with me throughout the years. She helped me to respect the inner world of children more intensely. Zola gave me an understanding of how early events help to shape an individual's worldview, as they did mine.

Zola also informed me that there are times when we need to revisit, reframe and reconsider our early formation and challenge some of those beliefs. We may find that by doing so we uncover, discover and discard useless baggage and make room for precious memories that hold meaning and positive reinforcement.

I recently revisited Zola, thinking of how so many children of different races and cultures are cast as "different" and "other" these days. With them in mind, I added on to Zola's story.

I hope to turn Zola's story into a children's book one of these days.

***

Hi, my name is Zola. I'm six years old.

My name is from the Congo -- that's a place in Africa -- and it means "to love."

I'm different. The reason why I know I'm different is because people keep asking me "What are you?" I don't know what to say when people ask me that, but the first time somebody did, I went home and told my mommy.

"Mommy, today, somebody asked me 'What am I?' My mommy said, 'The next time they ask you that, you tell them, 'I'm just a pretty little girl.''"

Well, the next time it happened, I did just what my mommy said. When somebody asked me, "What are you?" I said, "I'm just a pretty little girl."

Then they said to me, "No, not that. I mean, are you Black or are you pink?" And I said, "I don't know, I'm just a pretty little girl."

One day I saw my uncle, he's always asking me about school. "How's school, baby?"

I said, "Uncle, people keep asking me 'What am I?' My mommy said I should tell them 'I'm just a pretty little girl.' But when I did, they said 'Am I pink or Black?' But I don't know."

My uncle said, "What they saying to you don't matter none, you just keep telling them what your mama told you to say."

So, the next time somebody asked me "What are you?" I said just what my mommy and my uncle told me: "I'm just a pretty little girl." And they said, "No, not that. Are you a Creole or a Mulatto?" I don't know, I thought, what's a Creole or a Mulatto? I didn't have an answer.

Then one day I saw my auntie. I asked my auntie, "What's a Creole?" My auntie asked me why I was asking her that. I told her somebody asked me if I was a Creole. My auntie laughed and said, "You ain't no Creole, girl, now go on outside and play."

I went to my mommy and said, "Mommy, people keep asking me 'What are you?' I told them what you said -- that I'm just a pretty little girl. But they keep asking me stuff, like, 'Are you pink or Black? Are you a Creole or a Mulatto?' I don't know what they mean. Uncle said what they asking don't matter none. Auntie said I'm not no Creole. Am I a Mulatto, Mommy? Mommy, what's a Mulatto?"

Mommy said, "Baby, listen. You are Momma's baby, and you are a pretty little girl, and all those other questions people keep asking you don't matter. You just keep telling them what I told you -- you're just a pretty little girl."

Oh, well, my name is Zola. It's from the Congo, that's a place in Africa. It means "to love," and I'm different.

You want to know why I'm different? Cause being just a pretty little girl just ain't enough.

MORE FROM OUR RACE IN LA SERIES

- Don't Turn My Community Into COVID-19 'Trauma Porn'

- A Latino 'Gringo' On Straddling Two Cultures, Never Enough Of Either

- Life Beneath Hollywood's 'Bamboo Ceiling'

- Boricua At Home, Black In The World: An Afro Latina in LA

- As A Black Nurse At The Pandemic's Frontlines, I've Had A Close Look At America's Racial Divisions

- 'What Are You?' 'Are You Adopted?' A Biracial Black Woman Gets Real About The Questions People Have The Nerve To Ask

- Reading While Black, And Other Ways To Court Trouble

- Reparations And Reinvestment: Contemplating The Proverbial '40 Acres And A Mule' Today

- Claiming My Dignity On A San Fernando Valley Street

- The Day My Brother Learned To Fly

- In The Process Of Becoming American: A Proud Son Of Immigrants Reflects On His Family's Past And Future

- 'Black Enough?' Mixed Musings On My Skin Color, Hair, and Heritage

- How To Participate In Our Series

***

Time passes by, and people still keep asking me "What are you?" and I keep telling them the same thing. I'm just a pretty little girl.

But now the words they use are different. They say "Are you a half-breed?' and "Are you mixed?" Mixed? What's mixed? And what's half-breed?

I asked my Mommy to explain these words to me, but she says, "Don't pay that no mind, baby - you're just a pretty little girl, you're momma's baby and I love you...and that's all you need to know."

One day a new girl came to my school. She looked different than my other friends at school. She had a scarf wrapped around her head, and she never took it off. Not in class, not at lunch, not even when we went out to play. She wore it all day long.

One day, during recess, some of my friends asked her "What are you?"

When I heard my friends ask her that, I ran over, cuz I wanted to hear what she said. How would she answer the question people asked me? Was she a Creole? Was she Mulatto? Was she half-breed? Was she mixed? Was she just a pretty little girl, like me? Oh, I just needed to know so bad.

I waited and I waited. I needed to know the answer. Finally, she said, "Why do you ask me such a ridiculous question? What am I? I am a human being, just like you. You see me as different. I see me as who I am. My name is Habibi, it's Arabic, and it means 'loved one.'"

I stood there and just stared at her. How could this be? Another girl, in my school, who's different too, and her name almost means the same thing as MINE!

After that day, Habibi and I are best friends. She's different, and I'm different. We are the two "different girls" in our school, and we're always together.

Habibi tells me all about the country her family came from that's far away. We talk about all kinda stuff like the food we like, the games we like to play, the shows we like on TV and how people keep asking us stupid questions...like "What are you?"

Habibi taught me a new word. It's called "unique." She said it's like being different, but better. The way she said "unique" sounded way better to me than different. I like being unique, and I like being different. You wanna know why? Because being different and unique is something special. I feel special because I'm different and unique.

People still keep asking me "What are you" and now I tell them "I'm unique" or "I'm special." I like telling people that cuz when I do, they don't ask me more questions, or say words I don't understand because they think I'm different. I understand now why they ask, cuz I wanted to ask my friend Habibi questions too, like about the scarf she wore. But when we became friends, I didn't care anymore, all I cared about was that she's my friend.

My name is Zola, I'm six years old. My name is from the Congo, that's a place in Africa, and it means "to love." My best friend is Habibi, her name is Arabic, and it means "loved one." We are unique, and we like being unique, cuz being unique is something special.

People think we're different, but that's because they just don't know how special we are.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Leilani Burrell-White has worked in the counseling field for more than 30 years. She holds a Master of Science in human services management and a Master of Arts in professional clinical counseling. She presently holds a management position with a private agency within the foster care industry. She is a mother and grandmother who loves kids and has worked with children in the foster system, with teenagers, and with adults battling substance abuse.

Leilani is rooted and grounded in social justice for all people. Her early life experiences led her to take a direction where she wants to serve those who are disenfranchised. In addition to her full-time job, Leilani leads a class on sexual and reproductive health for teens, and is in the process of becoming a licensed professional clinical counselor.