It was starting off as a good day on June 25, 2020.

I had gotten in an early-morning bike ride. My energy was up and I had worked up an appetite. My wife had decided to sleep late, and I was basking in the solitude of the house. I was at peace as I started to prepare my breakfast.

-

From June 2020 to July 2021, we published your stories each week to continue important conversations about race/ethnicity, identity and how both affect our lived experiences. We now have a new series Being American, which is again soliciting your essays.

-

Read:

I turned on the radio in the kitchen to listen to KPCC and NPR, as I do most mornings. Morning Edition was on, and Attorney General William Barr was being interviewed. Near the end of it, the subject of race was introduced.

I'll say it up front, I'm not a fan of Barr. I've questioned his judgement and character. But I was nevertheless eager to hear what tone our nation's top attorney would establish.

I'd never heard Barr address the topic of racism. So I listened closely. I stopped making my oatmeal and my special fruit concoction to give my full attention to his answers.

Then, he got a question along these lines: why is it that statistically, Black men in the United States are much more likely to be shot by the police than other groups?

I was hoping Barr would comment on some causative factors, perhaps offer some idea of how to work in earnest to combat this pervasive issue. Instead, I heard in Barr's answer a callousness, and a complete lack of desire to acknowledge that the disproportionate killing of Black men by law enforcement is even a problem.

And I was surprised by my naiveté in having hoped that Barr would actually demonstrate a modicum of sensitivity to the current social climate that has brought the Black Lives Matter Movement to the fore.

Barr quoted some statistics that I questioned, based on other recent reports I have seen and experts that I've heard speak on this topic. He began by saying that 8,000 Blacks are killed every year, and of that 8,000, eighty-five percent of those are by gunshot. He went on to say, "Virtually all of those are Blacks on Blacks."

He continued, going on to say that "there are many whites who are shot unarmed by police." (The rate at which Black people are killed by police in the U.S. is more than twice as high as it is for whites.) Barr referred to the 8,000 Black deaths again -- but added that it happens "by crime in high crime areas" and faulted the media for not giving that fact attention.

His overarching theme seemed to be that Blacks, not police practices, are the etiology for the rate of violence against Blacks.

Well, his comments had a direct hit on my good day.

Now, instead of my endorphins kicking in to energize me, they jolted me back to my encounters with the police growing up as a young Black man in Los Angeles. It elicited a feeling I used to have any time it came to my dealings with the police -- a feeling of us versus them.

Momentarily, I felt physically sick.

MORE FROM OUR RACE IN LA SERIES

- Rising Above: How I Found My Voice To Push Back Against Stereotypes, At Work And In Life

- Reading About Anthony McClain Felt Like Reading My Own Obituary

- 'Who Invited Miami?': An LA Transplant On The Rules of Racial Division -- And How We Can Bend Them

- 'We Don't Hire Colored Girls': After A Job Rejection In 1956, A Young LA Telephone Operator Began Kicking Down Doors

- An Education In Becoming Whole Again: How My College Experience Taught Me To Love My Blackness

- What It Really Means To Amplify Black Voices

- Raising A Black Boy In America When You're Neither Black Nor American

- Lessons Learned While Being Black: 'I'll Never Be Above Scrutiny'

- The Hidden Cost Of Inherited Blackness

- Jogging While Black: 'And Still They Crossed The Street'

- Black And Tired In This American Newsroom

- Conflicted: A Black Journalist's Reckoning With Her Race, Family And Police Brutality

- How To Participate In Our Series

The U.S. Attorney General seemed to be dismissing the excessive violence perpetrated by police against Blacks. I was repulsed by the smugness and complete disregard of Black suffering in his answer, an attitude that has become sadly familiar to me.

It hit home, because throughout most of my adult life, I've been subjected to police actions firmly rooted in the same kind of systemic racism that I heard in Barr's answer. Hearing his words caused me pain and sadness as it forced me to think of how two generations have reached adulthood since my troubles began with the police -- and the problem continues.

Those old feelings I would have back then -- anger, helplessness, a resolve to stand up and a hopefulness to overcome -- came rushing back and hit me like a cold shower.

It's something you feel down to your bones. I began to think of those two generations after me and those before, of countless men and women, all having had to deal with attitudes of enforcers like Barr. Here I was in the comfort of my own home, but those feelings flowed out of me nonetheless.

Now imagine how they get amplified for me, and those like me, when we have to deal with those oppressive attitudes whenever we face the police in the streets.

Barr spoke of Black-on-Black crime as if it is the only way of life Black people experience. That was not my experience in my community, nor was it for most of the Black friends, associates, and family in my life orbit.

My problem was the police, not Black people.

DRIVING TO WORK, 1978

At the time when I was a graduate student, I had to gain clinical hours for my work in psychology. I worked the late shift at a hospital that happened to be an area where the police did not seem to think Blacks belonged.

During my time working there, it seemed I was stopped at least once a week. It wasn't that frequent, but it felt like it. All I was trying to do was get to work on time. I had to be sure to leave my home early every day, so in case I was stopped I wouldn't be late.

My mother would always worry about me and tell me if I were stopped, to please keep my mouth shut. She knew I was one who would stand up for myself. That is how she raised me.

This one particular pull-over, the premise was I was being stopped because one of my tail lights was out. After the white police officer who approached me told me why I was pulled over, I began to ask questions about the stop, and asked if I could see which light was out.

The officer told me to shut up. He told me they needed to run my name through the system for warrants, violations, et cetera. Now, I never raised my voice, but merely requested clarification as to why so much action was being taken for a light bulb.

At that point, I was instructed to exit the car.

I was now on the curb, standing next to one of the officers. I continue to speak and request again to see that, in fact, I had an inoperable light.

At times, when I speak, I use my hands. Again, the officer told me to shut up and keep my hands still. I retorted that I had a right to express myself in my natural way. He then placed his hand on his gun and made a movement as if he was going to pull it from his holster.

He told me that if he had to tell me again to keep my hands still and shut up, he would blow my brains out. Finally, the other officer came back from the patrol car and informed the officer standing with me that there was nothing on me. To my surprise, when I finally got the other officer to show me the tail light, it actually was out. I tapped the light, and it came on. It was just loose. They still wrote a citation for me to go to their inspection site to get it reviewed.

I did not mention to the other officer that I, an unarmed man, was threatened by his partner over questioning which light was out.

I called this behavior police harassment back then. The word "harassment" now seems mild and inadequate as a descriptor. It tends to suggest an individual who may occasionally take isolated action outside of acceptable behavior. But in the years since my young adulthood, I see that the disproportionate mistreatment of Blacks by police has become deeply entrenched in law enforcement as an overall approach.

At least after that harassment from my youth, I had some hope. There was hope that, at some point, the rogue cop would be dealt with and removed. I can no longer hope for that, or dismiss it as the action of a few rogue cops, something that Barr also intimated in the interview as part of his response.

I still had that hope after another time I was stopped by what I called a rogue cop for driving while Black. It wasn't called that back in the 1970s, but that's what it was.

It was early evening. I was headed home driving what some might call a vintage collectible car -- a 1958 Cadillac Coupe. I was doing nothing wrong for this officer to stop me, other than being Black.

I was driving west. He was going east. As he passed me, peripherally I could see I had garnered his attention. I knew instantly he would turn and come after me. Sure enough, I soon saw the red lights in my rearview mirror. He pulled me over. I asked why I was being stopped. His response? Because he wanted to stop me, he said.

I asked him, "What law have I violated?" He then demanded that I exit the vehicle. He checked me for weapons, and then told me to stand on the sidewalk. He took his flashlight, shining it into my vehicle, and looked under my seats and in the glove compartment. He found nothing, and told me I could go.

I told him that I knew what he had just done was illegal. On this moonlit summer night, he looked me in my eyes, and focused his flashlight on his badge number so I could see it clearly.

He said with impunity dripping from his words, "If you don't like it, here is my badge number."

He then drove off into the night.

BLACKNESS AND HUMANITY

Back then, I could not have imagined that the kinds of problems that I and others had with the police would continue, unabated, for each successive generation of Blacks after me.

Blacks have had to get stronger to protect themselves because, it seems, with each successive generation of police officers, the authorities become more militaristic. And Blacks continue to take a big hit as a result. As I listened to his words on the radio, Barr reinforced for me that I can no longer consider any reason other than systemic racism as the overwhelming reason as to why these inequities against us have proliferated, generation after generation.

He is just the latest leader in law enforcement to promulgate the theory that Blacks are the cause of their problem with the police.

His answer avoided the issue of racial disparity, was devoid of acknowledging the humanity of Blacks, dismissed our individuality, and demonized us by manipulating some arcane statistics. And he never answered the question as to why Blacks are more likely to be shot by police than others on a per capita basis.

I can answer it for Barr: The majority of my interactions with the police have been for no other reason than the color of my skin. It was me in a neighborhood they decided I didn't belong in, or driving a car that I couldn't possibly be in possession of legitimately. And that is how they were trained to police Blacks.

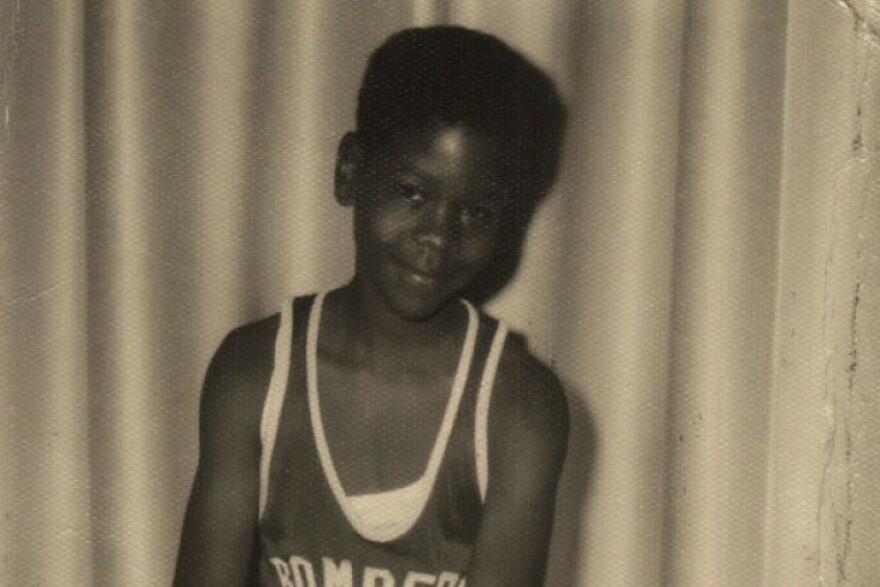

As do millions of Blacks, I come from a decent and supportive extended family, both maternal and fraternal sides, who value education, served in the military, competed in the Olympics, and achieved executive levels in government and business.

We have attained what is considered successes when measured by any American family standard. Yes, we have some family members who have gone off the rails. But what family doesn't have that?

However, my commendable family heritage, college education, successful professional career, dedication as a father and husband, and contributions to my community mean nothing once I am pulled over by the police.

What I learned many years ago: never forget that none of it is considered as even a possibility by the police when I am stopped. I never fool myself that they will see me as a family man or just as a citizen. It remains in my psyche with each traffic stop that I could be the next one to lose their life or be hurt. The possibility that I am a law-abiding citizen seldom seems to enter the equation during my encounters with the police.

In 1965, I was a little boy unable to understand what was happening in Watts when citizens rebelled, and the city burned. I was fearful of what I saw being reported on TV.

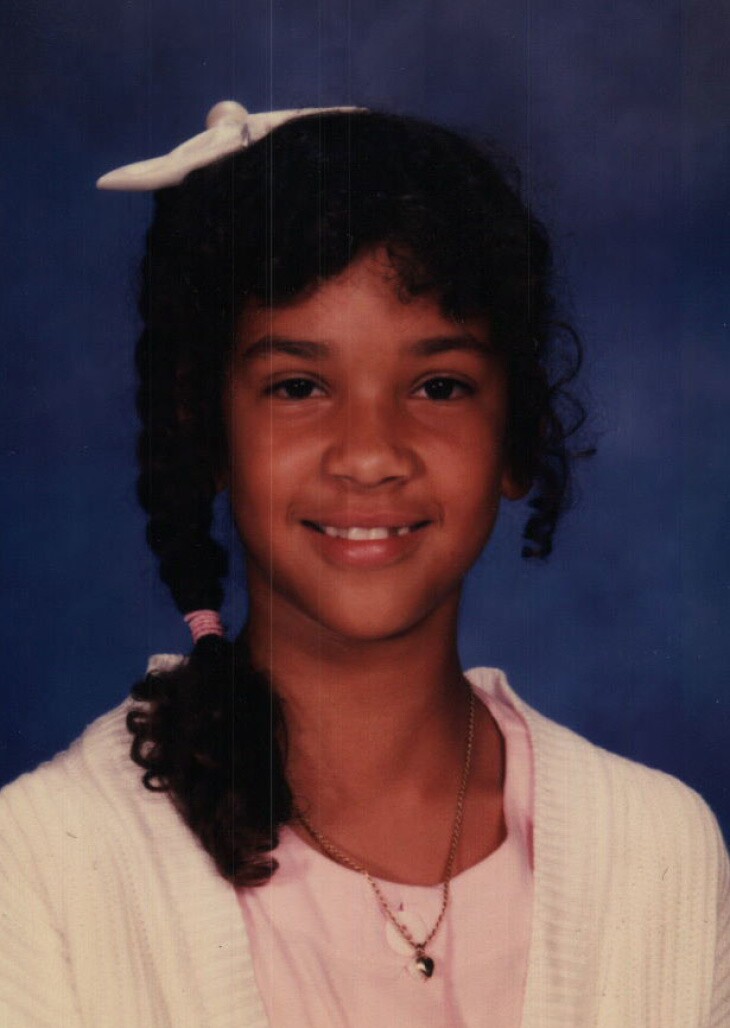

Years later, as a little girl, my daughter had the same fear as the city burned again in 1992, after the four officers who beat Rodney King were acquitted. That fear is wrapped in the emotions that begin to register when, for the first time, a child learns the police can hurt them, instead of helping them.

Blacks are often viewed as a threat, or as something less than others, or sometimes both. In dealings with the police, the humanity of the individual Black person is mostly nonexistent. It doesn't feel like they see us as someone's daughter, mother, brother, sister, son or father.

Not all, but most of my exchanges with law enforcement have felt like that. I can hear it in their tone. I see it in their eyes. I am not a person but rather, in that moment, only a mass of Blackness. I become just a symbol of inferiority to that officer.

In the years that followed Watts, I grew from boy to man, from single man to family man under law enforcement leaders like William Parker, Ed Davis and Darryl Gates, three Los Angeles Chiefs of Police with some very questionable positions on race.

Note, I did not call them racists. There is sufficient documentation of public actions and racist statements available from each of them for anyone to draw their own conclusion. So, I leave that to others. However they, like Barr, have been prime proponents of how systemic racism has been allowed to flourish.

Under Parker, we had the Watts Insurrection stemming from a traffic stop gone bad. It was the tipping point for what I mentioned earlier: that Black people realized they had to get stronger and stand up. Under Gates, the Los Angeles Insurrection of 1992 is also directly linked to a traffic stop, and the systemic racism in policing that was growing ever more paramilitary.

We do not need more law enforcement leaders like Parker, Davis, Gates, or Barr. We deserve better so that kids won't have the kind of fear for our community that I or my daughter felt.

Those police stops -- driving while Black -- continued for me for many years as I went from young man to mature man. There were so many I can't even recall them all. The good news is I can say that while the pull-overs didn't completely stop, the frequency did decrease as I aged. But while my stops were less frequent, when I was in a place deemed not for me, it was the same as 30 years ago. The officer just saw Black.

I saw the same look in the eyes. The same tone of voice. From time to time, I have actually been able to break through that, and have them speak to me as an individual.

The problem is that I shouldn't have had to work so hard to achieve that. In fact, I shouldn't have to work at it at all.

'COMMON TO A SYSTEM, AFFECTING THE BODY GENERALLY'

Barr was done talking. The show had begun another segment. I took a deep breath.

I was exhausted from my mental excursion back in time. I hadn't even had my breakfast. I got back to trying to regain that good day I had started. Time to focus on that oatmeal combo to fuel my day.

As I began to eat, I took some satisfaction in thinking how blessed I was to have made it through so many negative encounters with the police. In his interview, Barr had criticized the media and activists for demonizing all police as racists. That is how he understood people calling out systemic racism. However, I have lived through it and know better.

To understand systemic racism, one must first understand that it is not about calling individuals racists. Rather, it illuminates how ill-conceived constructs, beliefs and assumptions can negatively influence how you treat another human being. It happens in many societal environments. However, I am just speaking of policing because of what Barr elicited in me.

There is something about my Blackness, and being connected to a history of people who were enslaved, that allows an approach to law enforcement where an officer thinks it's even close to okay to threaten me, unarmed, with blowing my brains out over a tail light or stop me because they feel like it. As if it's their right.

Systemic racism is why our Attorney General, in the interview I heard, chose to respond to a question about the tragic unnecessary loss of Black lives or harm by using statistics, instead of exhibiting compassion or maybe just a bit of decency about the matter of undue violence against these fellow Americans.

Systemic racism in policing means the system does not allow for consistent equal treatment and protection of Blacks in the communities in which they live.

Barr implies we shouldn't blame all police because of a few bad apples. For me, that is just another way to use the antiquated "rogue cop" excuse that I no longer believe to be valid. It is now about a tree that has rotted, as I see it. Ultimately, all the apples can be affected. The good ones and bad ones will be tainted to varying degrees.

Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary defines systemic this way: Common to a system, affecting the body generally. In this case, the body is the police department.

I believe that Barr is most likely blind to the fact his comments were rooted in systemic racism. Systemic racism places Blacks as the enemy, not worthy of fair consideration or respect. When I hear someone try to reduce us to statistical, blame-filled shadows like Barr did in that interview, I think of those thousands of everyday occurrences that people like me have with the police -- disrespectful, oppressive, and suspicious interactions.

Ultimately all too often, on one ordinary day of business as usual, it will result in that unjustified shooting and/or killing. The shooting of a Black person is more likely because of the disease of systemic racism, plain and simple. In the weeks since I heard it, Barr's interview has only strengthened my resolve about it being the primary cause of poor policing.

From what I, my family and friends have experienced over the years, cumulatively it can feel as if the police are not there to protect as much as they are to occupy our communities, like troops in a foreign land. The choice Attorney General William Barr made to not really answer a question about a very real phenomenon regarding violence against Blacks is an excellent example of how the disease of systemic racism works.

Whether knowingly or unknowingly, the disregard for the humanity of Blacks is what propels it. For the police, some are more infected by it than others. For Blacks, any wrongful or unjust action taken against us is based on the premise we are not worthy of anything better.

This year, the tragic deaths at the hands of law enforcement in Minneapolis, Louisville, Kenosha, locally in Pasadena and just recently in South Los Angeles have and continue to spark a greater awareness of the problems my community has long experienced with policing. There seems a newly discovered understanding of the action America needs to take against systemic racism.

So, I will hold onto that same hope I had after that after the "rogue" cop shone the light on his badge all those years ago, or my recent hope that Barr would give a thoughtful answer about racism and Black deaths at the hands of police.

I do hope that one day, those recollections that I have of my own police mistreatment will become solely historical. I am optimistic that we will get better answers and solutions than Barr provided, and the experiences I recounted will no longer be an acceptable legacy for more generations to endure.

Perhaps, we are on our way to some good days ahead.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Keith Taylor has strived to be a good son, husband, father and community contributor. With that as his North Star, paired with his faith, it has guided him along his life path. When he has done those roles well, everything else has fallen into place.

Keith has been blessed to have been able to pursue professional endeavors as a human resources executive, communications specialist, psychotherapist, educator, executive coach and music promoter. Most recently, he has returned to creating art, a passion from his college days he had set aside for a period of time.