The question of how to pronounce some of L.A.’s most quintessential names — the streets, neighborhoods and destinations that make up our everyday vocabulary — is much more complicated than it should be.

That’s because there’s no “right” way to say a lot of them. Is Los Feliz lahs-FEE-luss or lohs-feh-LEEZ? Is Angeleno an-jeh-LEE-noh or an-jeh-LAY-noh? Ask around and you’re not likely to find much consensus.

Finding the original pronunciations of some of our city names is a task in and of itself — were they English-given titles meant to evoke the city’s Mexican/Spanish roots? Spanish names bestowed on native villages by missionaries? Or does the proper pronunciation of words like “Angeleno” fall somewhere in the hybrid pond of a specific brand of L.A. Spanglish?

Unfortunately there weren’t any true crime podcasts in 1781 or 1850, so we don’t have a super clear way of knowing exactly how any of the “original” L.A. towns or streets were actually pronounced.

That’s why we’re turning to you, dear readers. What pronunciations do YOU use? Take this tour through some of L.A.’s most confounding names — some with one definitely correct people-will-laugh-at-you-unless-you-say-it-like-this pronunciation, and others that are...a little fuzzier to nail down — to see where your L.A. dialect falls.

How Did We Get Here?

Most of the confusion about local speak comes from the history of how L.A. came to be, which is a lovely tale of friendship, hand-holding, and cross-cultural kumbaya. Just kidding, it’s a lot of colonialism, slavery and, uh, genocide.

In the late 18th century, the area now known as Los Angeles was inhabited by a particular mix of people and languages.

Spanish explorers landed on the California coast in the early 1500s and bestowed some of their country’s names on the landscape — think San Pedro, Santa Monica and Santa Catalina Island. But it wasn’t until much later that they actually settled there; the first Spanish land expedition through California wasn’t until 1769. That’s when the Spaniards, particularly priests and soldiers, began to actually colonize the area, building missions and forts (presidios) to establish religious and military control over the region, bringing with them a rigid class system that put “pure blood” Spaniards at the top (surprise!) of the food chain.

“Pobladores” were a second wave of Spanish colonizers who came from the Sinaloa region of Northern Mexico in the late 1700s via three wagon trains to settle a new pueblo, which was one prong in Spain’s master plan to fully take over the terrority. The pueblo would provide a secular, civilian presence, while the missions would handle religious domination. The group of original pueblo settlers was made up of 44 individuals, who were a mix of indigenous Mexicans, “mestizo” and “mulatto” immigrants (mixed-race Mexicans with indigenous, European Spanish and black African parentage...via the Carribbean slave trade).

Of course, before these outside groups set foot in Southern California, the region was inhabited by the Tongva people, whom the Spanish dubbed “Gabrielino Indians.” Historians estimate that there were about 100 native villages in the area at the time of the pueblo, including the central Tongva town of Yang-na, which some academics say is the earliest site of the land that would later become downtown. There were also extensive trade networks with other native tribes, like the Chumash, who hailed from the area that is now Santa Barbara.

(If this is confusing, you can thank imperialism.)

As early as 1781, when the Pueblo de Los Ángeles was built, these groups coexisted alongside one another, trading goods and even intermarrying. The spoken language in the earliest version of L.A. then was at its most “authentic”: a mash-up of indigenous Tongva words, Spanish/Castilian dialects and possibly even some indigenous Mexican languages brought to the area by the pobladores.

When the first Anglo immigrants started to arrive in the area in the 1820s and ‘30s, Spanish was the dominant language (the territory was still part of Mexico), and they typically learned enough to communicate with their neighbors. Some of them even rechristened themselves with Spanish names: Scottish adventurer Hugo Reid, for example, became “Perfecto Hugo Reid.” These white men in early Los Angeles were commonly known as “gringos” and even wrote letters in Spanglish.

In 1850, the city council appointed a man named Edward O.C. Ord to create the first official map of Los Angeles. He gave many streets both Spanish and English names, like Esperanza/Hope Street and Loma/Hill. Legend has it that he named Spring Street after a young Spanish woman named Trinidad de la Guerra, whom he nicknamed “mi primavera,” or “my springtime.”

Even the first California Constitution was written in both Spanish and English, and decreed that all laws be published in both languages.

“Being multilingual was a feature of L.A. life for the first three decades, after it became part of America,” said D.J. Waldie, local cultural historian and author of the essay collection “Where We Are Now: Notes from Los Angeles.”

And that separated it from other parts of the state.

“Unlike Northern California, where you had this huge influx of English speakers during the Gold Rush,” said Nathan Masters, a historian at USC libraries, “Los Angeles remained majority Spanish-speaking until the 1880s, when you had this huge influx of people from the Midwest, as well as the East Coast.”

The Midwestern boom happened in large part thanks to a successful and long-running marketing campaign that began in the 1870s and was designed to sell “scrubby” California land that no one really wanted to buy, said Waldie. The campaign touted other benefits — healthful living, economic opportunity, wide open spaces and a general exoticness. One strategy to make that land more exotic was to give places Spanish-sounding names, even if those names weren’t necessarily correct Spanish.

Some places in Southern California still have distorted or misspelled “Spanglish” names, like Marguerita Avenue and Alhambra (which was anointed by an Anglo man named Benjamin Wilson who chose the name at the urging of his daughters, who were reading a book about the legends of Moorish Spain called “The Alhambra”). “It was designed to make Southern California feel more romantic,” Waldie said. A similar train of thought later led to the regional embrace of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture and palm trees.

As more white Anglo families from other parts of the U.S. migrated to Los Angeles to enjoy good weather and cheap land, they branched outward from downtown to settle and start towns in surrounding areas. That’s why a lot of the smaller cities in L.A. County, which were founded in the 20th century, have English names instead of Spanish ones, like Burbank (named after a New Hampshire-born dentist), Huntington Park (named for Henry Huntington, a railroad builder and book collector from New York) and Culver City (named by Harry H. Culver, who came to L.A. via Nebraska).

Over time, the native Tongva language stopped being spoken (the result of a massive campaign of cultural repression), although some linguists are now reviving and reclaiming it.

This takes us all the way to the present day where, according to census estimates, Latinos make up over 48% of the population of Los Angeles.

All of this messy history explains why scholars of Southern California history and language advocate an open-minded approach to local pronunciation, rather than a prescriptive one, said Reynaldo Macias, professor of Chicana/o studies and sociolinguistics at UCLA. “Some of these local indigenous terms were Spanishcised and then Anglicized,” he said. “So it’s complicated.”

Waldie agreed. “I think it’s important that we not try to find one precise, correct way to pronounce city names and places, because there isn’t any,” he said. “Language changes, continually.”

“What will be interesting in the future,” Waldie said, “is if an increasing Latino population — and number of Latino/a television personalities — gradually bring some modification to our pronunciation of Spanish words and names. Because they very much could.”

Los Angeles

The name of our fair city. Translates from Spanish to "The Angels."

You might be thinking, “Wait, this one is incredibly obvious.”

But like all good things, the pronunciation of L.A. is a lot more complicated than it may appear, historically speaking. The name Los Angeles is derived from the original name for the Spanish colonial pueblo that once sat in the area that would later become downtown — and get ready, because it’s a long one: “El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de la Reina de los Ángeles,” which translates to “The Town of Our Lady Queen of the Angels.” But even that name is historically controversial.

In 1835, the Mexican Congress changed “pueblo” to “ciudad,”making Los Angeles an actual city (on paper, although at the time there were probably only a couple hundred residents). And in 1848, that city became part of America.

At some point during that time, newcomers must have started saying law-SAN-jeh-leez, (which is how some Europeans still pronounce it — we’re looking at you, Brits) because in 1880, the city’s Chamber of Commerce issued this friendly reminder to residents: “The Lady would remind you please, Her name is not Lost An-jie-lees.”

As early as 1908, pioneering journalist Charles Fletcher Lummis launched a letter-writing campaign where he counted “no less than twelve [verbal] mutilations” of the city of Angels, law-SAN-jeh-leez being his least favorite. He preferred loh-SAN-geh-less. "There is no other city in the world whose inhabitants so miserably and shamelessly, and with so many varieties of foolishness, miscall the name of the town they live in," Lummis wrote in 1914.

In 1934, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names decreed that the official pronunciation should be the Anglicized lahs-AN-jel-us, which the L.A. Times was not pleased with, preferring the Spanish pronunciation, which they went so far as to print on their masthead to educate readers.

But even then, the name continued to be pronounced with different variations. Millions of people came to Southern California in from the Midwest, particularly in the 1920s and ‘30s, people who had never been expected to speak Spanish before. “They had no patience trying to twist their tongues around lahs-AHNG-heh-les, said historian D.J. Waldie, so they began to call it lahs-AN-jeh-leez or law-SANG-gleez.

According to the L.A. Times, in 1952, Mayor Fletcher Bowron assembled a jury made up of radio announcers, lawyers and writers, to decide on the proper pronunciation of the city. They settled on lahs-AN-jel-us, which was apparently a real bummer for Bowron, who was a big fan of the hard “G.”

Alas, trouble pronouncing the city name ensued until well into the 21st century. In 1950, L.A. police chief William H. Parker said loh-SAN-geh-les, with that hard “G,” on a radio show called “On the Beat.” Sam Yorty, who was mayor of L.A. from 1961 to 1973 (and also a Midwesterner, originally from Nebraska) also famously called it loh-SAN-geh-les. In 1968, Arlo Guthrie rhymed Los Angeles with “keys” and “please.” And in 2011, Texas Governor Rick Perry followed suit with a strange fusion of the hard “G” and the British accent, which sounded something like loh-SAN-guh-leez — the L.A. Times described that pronunciation “as though it contained a hard “G” and rhymed with “fleas.”

do

Angeleno

Term used to describe a resident or inhabitant of Los Angeles.

Angelino and Angeleno have always contended with one another as the go-to term for residents of Los Angeles. Based on spellings found in books over the years, it seems Angeleno dominated before 1930 and Angelino took over after. By the year 2000, the battle levelled off and both descriptors were used interchangeably.

But according to local historian D.J. Waldie’s research, both of these pronunciations are technically incorrect. The historically accurate pronunciation is actually ahn-heh-LAIN-yo, spelled Angeleño. Waldie said that’s because it’s how the name for city residents was first written in 1888 by the two authors of “California of the South,” a traveler’s guide to the topography, climate and history of the region.

The ñ fell out of favor in the late 1870s with the influx of Midwestern and Anglo settlers who found it too troublesome to type the tilde — American typewriters didn’t have one, making it difficult even for those who did want to type it, so it eventually vanished from the lexicon.

Today, if you ask Google, the friendly digital voice still pronounces it an-jeh-LEE-noh. MacMillan dictionary agrees, as does Merriam-Webster, several YouTube videos and one country western singer.

Even more confusing? Two signs, one above the other, marking the historic area between downtown and Echo Park spell it two different ways: Angelino Heights and Angeleno Heights. In 2013, radio producer Kevin Ferguson asked luxury magazine Angeleno how to pronounce their own name and got a “No comment,” so we may have to chalk this one up to a forever mysterious “inconclusive.”

Los Feliz

Trendy Los Angeles neighborhood, bordered by Griffith Park, East Hollywood, Silver Lake and Atwater. Known for independent restaurants and shops like House of Pies, Skylight Books, Alcove, and the Vista Theater.

This one is a real doozy, friends.

Los Feliz may take home the prize for the most controversial pronunciation in Los Angeles. In 2013, the L.A. Times called the debate over its pronunciation “timeless.”

Historian D.J. Waldie said the common Anglo pronunciation stems from the Midwestern takeover of Los Angeles in the late 1800s, which has confounded residents who often wonder if they should be using a more Spanish pronunciation. The Feliz in Los Feliz, however, isn’t the Spanish word for “happy” — it’s actually the last name of a Spanish dude.

José Vicente Feliz once owned the area east of present-day Hollywood. He was gifted the 10 square miles of land by the Spanish crown as a thank you for his service at the Pueblo, hence the name Rancho Los Feliz. Little did he know that houses on that land would sell for millions — or that one day in the year 2018, a student at a local Catholic school would grow up to become a British duchess.

Eventually the land was sold to the infamous Griffith J. Griffith, an alcoholic misanthrope who tried to murder his wife (yup) and spent two years in San Quentin. So 1896, amirite? Homebuyers were not pleased by his sullied reputation, which is why he eventually ceded most of the land to the city for a public park. Once the movie industry picked up, the area became a wealthy enclave known for expensive homes in the hills and quirky shops on Vermont Avenue. But that didn’t stop people from arguing over the name of the ‘hood on Reddit.

The Broad

Modern art museum in downtown L.A.

The Broad, which opened in 2015, was named after philanthropist Eli Broad, meaning it is definitively pronounced BROHD, not like the common adjective for something wide. If anything, the name makes for a quick way to tell when you’re speaking to an out-of-towner.

Villaraigosa

The 41st mayor of Los Angeles.

Having a name that’s tricky to spell and even trickier to pronounce can be a setback for someone running for office, but it seems to have worked out fine for L.A.’s former mayor (though maybe not during his 2018 gubernatorial run).

Whenever in doubt, there’s always a good ol’ mnemonic device to turn to. Villaraigosa broke down the pronunciation for NPR’s Karen Grigsby Bates back in 2005, when he won the mayoral election: “Via airmail, rye bread, gosa. Via-rye-gosa,” he said. Something for him to keep in his back pocket next time he runs for office.

Carvalho

L.A. Unified Superintendent, named in late 2021

Alberto Carvalho came to Los Angeles after a long career as an educator in Miami. He grew up in Portugal, before moving to the U.S. as a teen. He learned English and Spanish here, and he favors a very Anglicized pronunciation of his last name: car-VAH-lo.

San Pedro

Coastal area between Palos Verdes and Long Beach, home to the Port of Los Angeles and the L.A. Harbor.

In 1542, Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo became the first European to land in the area now known as San Pedro. He claimed the land for Spain on Nov. 24, the feast day of St. Peter of Alexandra, hence the name San Pedro.

"San Pedro is my pronunciation pet peeve," said Yolanda Ware, the facilities manager at KPCC, who read the pronouncer for this story. "It’s obviously Spanish" — which would make the pronunciation san-PAY-droh.

Ware did not grow up in San Pedro, however, and Doug Hansford of the San Pedro Bay Historical Society said that’s exactly how he would know she’s not from there.

"When we hear someone say san-PAY-droh," he said, "we know they’re not a local," adding that san-PEE-dro is definitely the correct pronunciation for the neighborhood, based on how residents have long said it. Even Spanish speakers who are from San Pedro, he said, say it that way. He’s not sure how that came to be, since there’s no official record, but he thinks it might have something to do with the dominant anti-Spanish sentiment in the years after the American Civil War.

Others suggest that the Anglicized pronunciation stuck because of San Pedro’s small-town feel — the area was an independent city until 1909, when residents voted to become part of Los Angeles. It’s possible that somewhere along the way, the funky pronunciation became a source of community identification and pride.

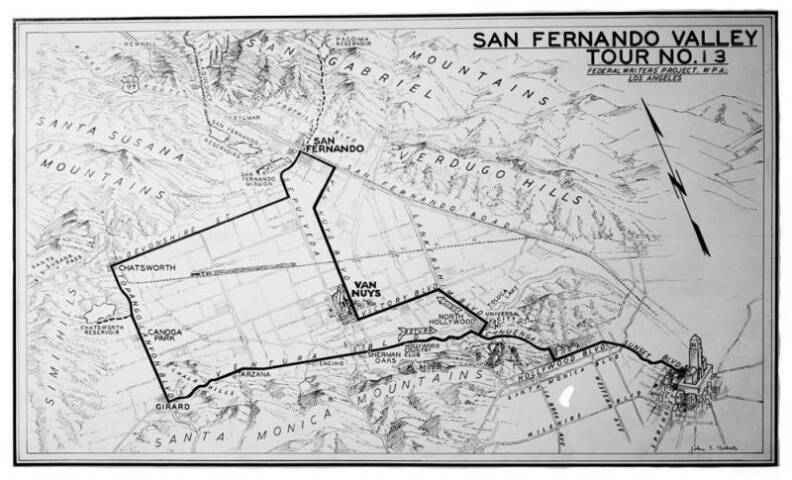

Van Nuys

Suburban neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley.

Van Nuys is named for one of the men who developed the area, Isaac Newton Van Nuys. It’s a Dutch name with a Dutch pronunciation. Van Nuys, the man, was a rancher and entrepreneur who at one point co-owned the southern half of the entire San Fernando Valley. He died in 1912, just a year after the official founding of Van Nuys the town (and just a few years before it would be annexed by Los Angeles).

Today, Van Nuys the neighborhood is known for being the heart of the Valley, home to a thriving porn industry and more than one attempt to secede and form its own city.

El Segundo

Neighborhood bordered by LAX and Manhattan Beach, known for its aerospace industry, oil refinery and power plant.

Despite the Spanish name, El Segundo was not named by a Spanish explorer (counterintuitive, no?). In 1885, the area was a rancho, made up of mostly uninhabited land used for farming. It wasn’t until 1910 that it was selected as the perfect site for a new Standard Oil refinery.

Richard Hanna, who had just finished a stint successfully running a refinery in Pennsylvania, was recruited to come west and build the new site for Standard Oil. It was his wife, Virginia, who named the area “La Segunda,” which was later changed to “El Segundo,” Spanish for “the second” to signify the second oil refinery in the state. (The first Standard Oil refinery up north in Richmond had already earned the name “El Primero,” although that name clearly did not stick.)

When the L.A. Times headquarters moved to El Segundo in 2018, columnist Steve Lopez noticed that people were consistently saying the name two different ways, ell-seh-GOON-doh and ell-seh-GUN-doh. He found that while most of his Spanish-speaking students said goon, most residents said gun, which could be because the area is 80% white and only 11% Latino. However several Spanish speakers also told Lopez that they pronounced it gun, so we’re going to have to call this one a draw.

Port Hueneme

Small beach city in Ventura County, known for surfing.

The official government website for Port Hueneme includes definitive pronunciation instructions, guiding visitors to wy-NEE-mee. The name is derived from a Chumash word, "wynema," which means "halfway" or "resting place."

The Hueneme name appears in several landmarks around the city — including the actual port, as well as the pier. In the spring of 2019, the city council briefly considered a proposal to rename the pier after a longtime council member, but faced fierce backlash from people who wanted to retain the homage to the city’s Chumash history. The council ended up dropping the proposal.

Rodeo Drive / Rodeo Road

Rodeo Drive: Famous two-mile street in Beverly Hills, known for its designer stores and tourists; Rodeo Road: Residential street in the Baldwin Hills/Crenshaw area of South L.A.

The more famous of L.A.’s "Rodeos," of course, is Rodeo Drive, which usually enjoys a shout-out in any movie or TV show set in Beverly Hills ("Pretty Woman" being the most prominent example). Its name comes from the Spanish-claimed property that later became Beverly Hills — "Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas."

Rodeo Road, on the other hand, bears the same pronunciation as that of the competitive cowboy sport. Nevertheless, that doesn’t stop starry-eyed visitors from getting confused — or winding up on Rodeo Road with a somewhat different shopping experience than the one they were expecting.

At any rate, those mix-ups may now be a thing of the past: Rodeo Road was officially renamed Barack Obama Boulevard on May 4, 2019 to honor the former U.S. president.

Cesar Chavez

An east-west avenue that runs through downtown and the eastside. Named after the famous Chicano labor leader.

Cesar Chavez has made many speeches over the years, but he’s been introduced in slightly different ways, depending on where he’s speaking and who is doing the introduction. When he spoke at UCLA in 1972, the chairman of the student speakers program introduced him as SEE-zer CHAH-vez. In a 1992 interview, Charlie Rose pronounced it SEE-zer sha-VEZ. (To hear a variety of non-Spanish speakers say the name, we present this montage of news anchors announcing Cesar Chavez Day.)

How did he pronounce it himself? “The first time he introduced himself to me, he introduced himself as SEE-zer,” said Dan Guerrero, a performing artist in the one-man show ¡Gaytino! who was friends with Chavez. He noted, however, that the name still has a Spanish language spelling, so a Spanish pronunciation would be completely justified.

"But it’s CHAH-vez, never SHAH-vez," he added.

Cesar Chavez Avenue (also seen as Avenida César Chávez in some signs), which runs through downtown just south of the 110 freeway, actually used to be called Brooklyn Avenue in the first half of the 20th century, when Boyle Heights had the largest concentration of Jews outside of New York. It later became Sunset Boulevard, and in 1993, the city council voted to change the name on the labor leader’s birthday, causing confusion among some white residents who had no idea how to pronounce it properly.

As it turns out other Chavezes have been similarly plagued by conflicting pronunciations.

Chavez Ravine

A primarily Mexican-American community near Elysian Park that was infamously cleared by the city for a public housing project, and was eventually developed into Dodger Stadium in 1959.

Historian D.J. Waldie said in his experience, it’s always been pronounced shuh-VEZ Ravine, as opposed to CHAH-vez Ravine. That’s because the neighborhood wasn’t named after labor leader Cesar Chavez, although it is quite close to Cesar Chavez Avenue.

"It was actually named after some other long-ago Chavez that once lived there," he said. That’s true. Chavez Ravine was named after Julian Chavez, a rancher who served as assistant mayor, city councilman and, eventually, one of L.A. County's first supervisors.

Julian Chavez died of a heart attack in 1879. Cesar Chavez wasn’t born until 1927. Two Chavezes, different pronunciations? Hard to say — Julian was born in Mexico and Cesar was born in Arizona, so it’s possible they had different accents. But since we couldn’t find any recordings of Julian Chavez saying his own name, that’s pure speculation.

Micheltorena

Windy street in Silver Lake, known for the rainbow-and-heart-painted staircase that runs up from Sunset Boulevard.

This street’s namesake is Manuel Micheltorena, brigadier-general of the Mexican Army and second-to-last governor of California under Mexican rule.

Micheltorena is the name of the Silver Lake street, as well as the famous staircase decorated by artist Corinne Carrey, and a local elementary school. A common mispronunciation is to call it something akin to Michael Torina, but we assure you that is incorrect. It’s more like Mitchell Torena.

El Sereno

Majority Latino neighborhood on the eastside of the city.

The area now known as El Sereno was once a Tongva village called Ostugna, according to the history compiled by the neighborhood’s historical society. An adobe was constructed there in 1776 by vaqueros from the San Gabriel Mission.

The area later became known as Rancho Rosa de Castilla (Rose of Castile), named for the wild roses that grew along the banks of a local creek. By 1900, the area was re-dubbed “Bairdstown” after the area’s primary real estate agent, George Baird — it wasn’t incorporated into the city of Los Angeles until 1915. Two years later, the name was changed again to El Sereno, meaning “quiet, calm place.”

After World War II, restrictive covenants barred Mexican American families from purchasing homes in El Sereno. But in 1948 those bans were lifted due to a Supreme Court decision. Now the area is majority Latino.

However, historian D.J. Waldie said he’s always heard the neighborhood pronounced ell-ser-EE-noh, never the Spanish way, which would sound more like ell-ser-EH-noh. Some scholars have referred to this pronunciation as “Chicano English,” an accent with specific roots in East L.A.

Tujunga

Neighborhood in the Verdugos region of L.A., bordered by Glendale, Shadow Hills and Sunland. Gained popularity in the 1970s as a bedroom community for workers commuting downtown.

The name “Tujunga” comes from a Tongva word Tuxuunga, which was originally pronounced ta-HOONG-ah with a softer “G” than the one normally used in the English language, according to Pam Munro, a linguist from UCLA. Munro is one of the few people who still speaks the Tongva language.

Cahuenga

Boulevard that runs north-south from the Valley through Hollywood, parallel to the 101.

Like Tujunga, Cahuenga also comes from a Tongva word, kawee'nga, which loosely translates to “place of the hill” or “place of the fox,” according to UCLA linguist Pam Munro. The name was meant to describe a Native American settlement in the San Fernando Valley, the exact location of which is unknown.

Later, in the late 20th century, farmers discovered a fertile ground for produce like bananas and lemons along the base of the Santa Monica Mountains (the area that is now West Hollywood and Beverly Hills). The location became shorthand for a suburban subregion dubbed the “Cahuenga Valley.” But by 1922, when the land ceased to be a farmland suburb and instead merged with the growing metropolis of L.A., the Cahuenga Valley title faded from public use.

The name lives on, however, in several other L.A. locations — the Cahuenga Pass, Cahuenga Boulevard and Campo de Cahuenga, an adobe house on the (former) Rancho Cahuenga where a peace treaty was signed between the U.S. and Mexico in 1847. The original adobe still stands — it’s now a historical monument in Studio City.

Taix

Beloved French restaurant in Echo Park. Originally opened in 1927 and quickly became the city's go-to spot for 50-cent chicken dinners.

The Taix family migrated to Los Angeles around 1870 from southeastern France, where they were sheep herders and bakers. Marius Taix Sr. built a hotel in 1912 in what was then downtown L.A.’s French Quarter. His son Marius Taix Jr. opened a restaurant in the hotel that served budget family-style French cuisine. It was so successful that the family opened its present location on Sunset Boulevard in 1927, which is now run by his grandson, Michael. The Echo Park location originally went by the name “Les Freres Taix” before it was shortened to "Taix."

Michael Taix told L.A. Weekly that most patrons still struggle to pronounce his family name. TAY is probably the most common, with TAYKS and TEX coming in at a close second and third.

So what should we be saying when referring to this classic L.A. spot? “It’s pronounced TEX, said Charlie Drake, a host who answers the restaurant phone on his shifts. “They taught me how to say it when I first started working here six months ago.”

Charlie is right, folks. Here’s your lesson de français: The correct pronunciation is in fact TEX. In French, when a word ends in “x” and it’s a proper noun, the “x” is spoken aloud. See: Aix-en-Provence. Do not see: “paix,” the French word for peace, which has a silent “x.”

Doheny

North-south street that forms the boundary between Beverly Hills and West Hollywood.

Doheny Drive was named for Edward L. Doheny, the man who drilled L.A.’s first successful oil well near the La Brea Tar Pits in 1892. Doheny’s success drove the city’s oil boom, and at one point he was even richer than John D. Rockefeller — although the later part of his life was plagued by an indictment in the Teapot Dome bribery scandal under the Warren G. Harding administration, as well as the mysterious death of his son, Ned.

The power and influence of the Doheny family name still live on in other parts of L.A., including Doheny State Beach, USC’s Doheny Library and Doheny Plaza in West Hollywood.

The name is Irish in origin, meaning if you think it’s said doh-HAY-nee, you are, sadly, mistaken — the Irish pronunciation is a solid Guinness pint of doh-HEE-nee.

Angelyne

Blond model, actress and singer known for her 1980s L.A. billboard campaign and her trademark pink Corvette.

The spelling is a bit non-traditional (Is Angelene the white bread to Angelyne’s baguette?). But while the L.A. icon’s name has tended to be on everyone else’s lips more than her own, there is solid evidence of her pronouncing it out loud — and, of course, it rhymes with “billboard queen.”

Leimert Park

Neighborhood and park in South L.A.

Leimert Park was named for its developer, Walter H. Leimert, who originally designed the neighborhood in 1927 as a subdivision for upper- and middle-class families. Thanks to a host of restrictive (racist) covenants that governed subdivisions all around L.A., its homes were off-limits to non-white residents for the next two decades.

The Supreme Court struck down those covenants in 1948, and in the decades since it has become a majority black neighborhood, known as a cultural center for the local black arts scene in Los Angeles.

A tip for remembering to pronounce “Leimert” correctly? It should rhyme with “alert.” If you’re pronouncing it like “lemur,” you’re doing it wrong.

Special thanks to all the KPCC and LAist staffers who lent their voices to the audio pronouncers: Matt Tinoco, Leslie Berestein Rojas, Sharon McNary, Andy Orozco, Myka Kielbon, Chava Sanchez, Yolanda Ware, Donald Paz, John Rabe, Nick Roman, Danny Sway, Mike Roe, Emily Elena Dugdale, Mary Plummer, Menaka Wilhelm, Lisa Brenner and Brian Frank.