-

We gave cameras to 12 Southern California child care providers, educators and caregivers and asked them to document their lives starting in the summer of 2020.

-

Join a live virtual event on June 17 and see the photos in real life at a series of photography installations throughout the region.

Virtually all children have experienced some kind of disruption during the pandemic.

“Sometimes when we think of trauma, we think of a car accident, or a fire or abuse or something very extreme, but the reality is that just transitions can have a really big impact on children’s well-being, especially for young children,” says UCLA clinical child psychologist Nastassia Hajal.

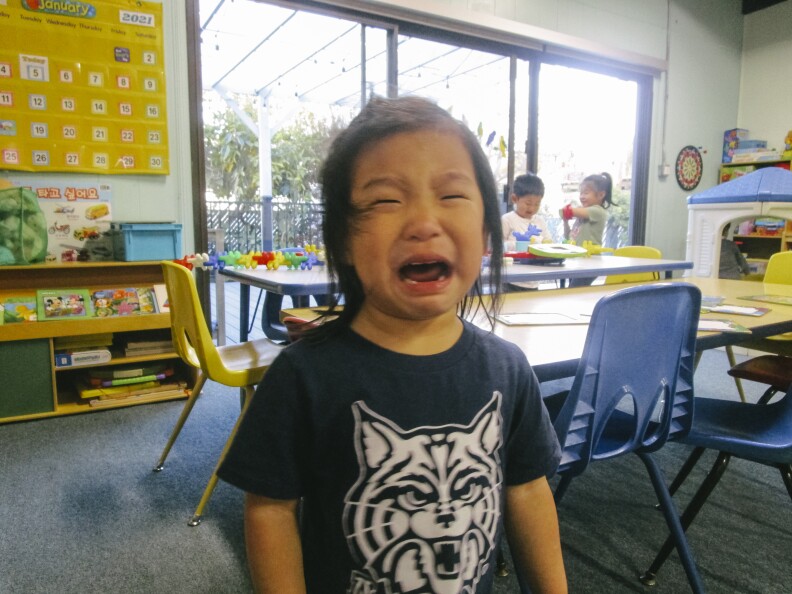

For young kids, all those changes pile on at an age known for Big Feelings, from face-down-on-the-floor meltdowns to unbridled joy.

“When a child has a feeling, it’s almost all-consuming,” says Children’s Hospital Los Angeles psychologist Marian Williams. “It’s physical...their temperature changes, their heart rate changes.”

She remembers her 12-month-old son shaking from head to toe the first time he saw the ocean.

“It took over his whole body, and I think that’s wonderful, but it can also feel really overwhelming if you don’t know what to do with that,” Williams says.

Child care providers witness these tidal wave changes in emotions every day, and have always had a critical role in helping children learn how to understand and manage their feelings. These foundational interactions can shape how children navigate challenges throughout their lives.

During the pandemic, child care providers and caregivers have also provided a critical sense of normalcy and routine.

Lancaster family child care provider Yvonne Cottage has noticed the weight of the pandemic on the kids in her care. They’d throw themselves on the floor or cry thinking about their parents who were at work.

“We just give them an environment where they feel open,” Yvonne says.

One thing she tries to do is look out for root causes of a child’s behavior so she can refer their family to resources, “hopefully before they get to the school system and [are] labeled as a ‘problem’ child,” she says.

-

Share a photo and your story with the hashtag #childcareunfiltered. We may even feature some of your community stories on LAist throughout the summer.

Each kid has a journal where they can draw, write out their feelings, or tear out the pages. On other days, she might invite them to take a few jabs at the punching bags hung throughout the house.

“We all have weird thoughts. We all have bad thoughts. Sometimes we can’t control them. But it’s what you do (that matters),” Yvonne says. “Those are hard things to teach young kids, but believe it or not, they get it.”

The youngest children sometimes don’t have the words to describe their feelings.

Jeanne Yu sets aside one specific area of her Gardena home day care where kids can cry and scream.

“At the same time, I help them try to figure out how to calm themselves down,” Jeanne says.

Maria Gutierrez’s 6-year-old grandson Charlie typically visited on the weekends, but he became a fixture in her home once the pandemic forced the closure of schools.

“My daughter lives in a small apartment,” Maria says. “So it’s very frustrating for him, with all that energy. He cannot stay in one place.”

She takes Charlie for walks through the neighborhood where he can say “Hi, friends!” to his favorite trees and roll on the artificial turf.

“They need someone to understand them,” Maria says. “Someone that they need to feel safe, they need to feel secure.”

“If I share my love with my students, if I share my love with other children that are not my family, why not share love with Charlie?” Maria says.

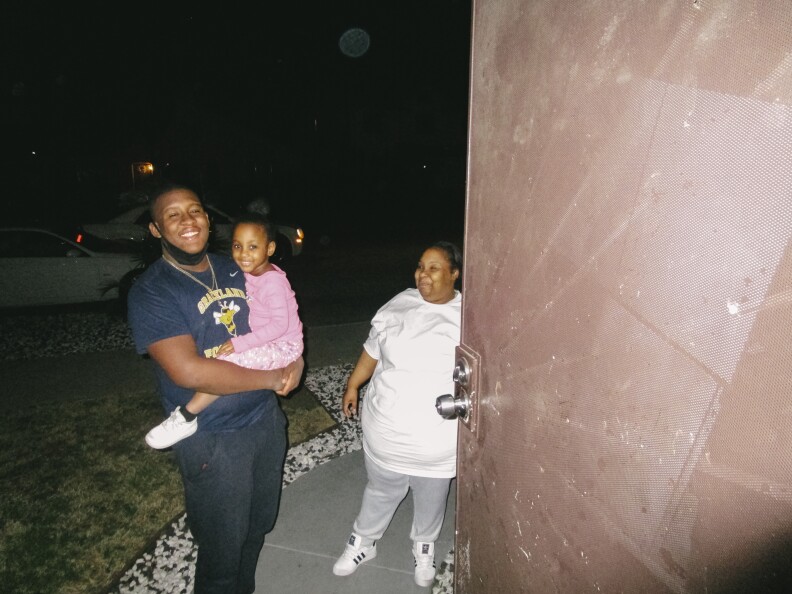

South Central family child care provider Jackie Jackson reserves four of her slots for children in the foster system.

In the little time she may have with each child, she tries to figure out what comfort is missing from their life. She says that because of the small, family-based setting, she can often give each child more one-on-one attention than they would receive in a larger, school setting. She often identifies a child’s needs and helps families find resources for them before they leave her care.

One young girl with speech delays was set on chewing through the family center’s books. Jackie found the girl a Lego-shaped teething alternative.

“She had an enormous amount of uncontrollable stress, internal,” Jackie says.

Gradually, using a puppet, Jackie says she was able to help the girl start to open up, and eventually began to coach her to use her words to express basic needs like asking for water.

For another young boy, Jackie says his mom was in another state. She’d set up a video call for them on her phone, and the pair would watch a movie or eat lunch together.

Jackie kept this routine going to help him maintain a connection with his biological family.

California child care providers have also created space for kids to experience joy during a time of uncertainty. Under their care, children have been able to play, celebrate birthdays, and mark holidays.

One day, Montebello family child care provider Susana Alonzo forgot it was a child’s birthday — but she managed to bake a pan of brownies, top it with a candle and they celebrated in the garden.

She says things like this are not much, but that it gives the kids a moment of peace and security, so that they might not feel everything is lost, “que no sientan que todo está perdido.”

In addition to providing stability for the children they care for, some child care providers and caregivers have extended their care into the community around them.

Early Head Start teacher Ruth Flores delivered art supplies and coordinated virtual scavenger hunts for members of her church.

“Even though it’s not much, it kind of lifted me up, cheered me up, that I made somebody happy,” Ruth says.

San Fernando Valley nanny Sofi Villalpando started making and distributing meals to unhoused neighbors in December.

“You get to know these people, and I’m like, how do I just stop? I can’t. So we continue to do it,” Sofi says. She’s delivered food 29 days this year and has bi-monthly meals planned through the end of 2021 — more, if donations allow.

Los Angeles Unified School District preschool teacher María collects donated books for her students.

And when diapers got scarce, South Central Los Angeles family child care provider Jackie stocked up and distributed them to her families.

“We are the jewels to the universe,” Jackie says. “We make a difference on the children and we make a difference in the lives of ourselves in our own community.”