Even as he lay dying on the side of a Southern California mountain – his lips blue, the color gone from his face – wildland firefighter Yaroslav Katkov wanted to push on.

“We’re getting to the top. We’re finishing,” his captain recalled Katkov saying after collapsing atop a ridge during a training hike in hot weather, according to state records.

Katkov’s speech was garbled. He tried to stand, but couldn’t find his footing. His body temperature was reaching dangerous levels. He was suffering from heat illness.

What happened on that sun-soaked July day in 2019 is one thread in a larger story about firefighter training in an era of intensifying heat. Over the past 18 months, more than 150 firefighters were sickened by heat exposure while working for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection — known as Cal Fire. More than a quarter of heat-related incidents — the largest category — involve firefighters who fell ill during routine training exercises, Columbia Journalism Investigations, KPCC and LAist found. Like Katkov, nearly all of these firefighters worked part-time.

The incidents, documented in Cal Fire’s workplace-injury logs, were specifically classified as heat-related and occurred between January 1, 2020 and August 3, 2021. CJI and LAist were unable to ascertain how typical the case numbers are. Cal Fire refused to say whether they were unusual or in line with annual totals for heat illnesses among workers over the past decade. The department declined to provide data that could put the numbers into a broader context.

CJI and LAist compiled less comprehensive data from internal Cal Fire reports on employee training injuries dating back to 2001, in addition to other state records. These documents show at least 14 other incidents that bear what some experts say are hallmarks of heat-related illness. In five of these incidents, the firefighters died.

All the firefighters succumbed to injuries not on the fire line in some remote California wilderness, but during required training. Many were decked out in full wildland gear — wearing long-sleeve jackets, pants and helmets while carrying heavy tools — and doing activities meant to simulate wildfire fighting — taking short hikes into the woods, for instance, or laying hoses up a mountainside.

All but one of the deaths occurred in temperatures ranging from 70 to 87 degrees. Four of the victims were incarcerated, participating in a state program meant to bolster firefighting forces that dates back to WWII.

Public health experts and federal workplace regulators agree that heat-related illnesses and deaths are 100% preventable.

Interviews with current and former Cal Fire employees, medical personnel and wildland firefighting experts, a review of hundreds of pages of government records detailing firefighter injuries and deaths and an analysis of worker heat death cases reveal multiple issues involving workplace safety during Cal Fire training activities. This is true especially for those who don’t work year-round, such as seasonal and incarcerated firefighters. Combined, they make up about half of the agency’s nearly 10,000-strong firefighting force.

Katkov’s death was exceptional in just how many institutional failures occurred during his hike, records show. But many of the other cases of heat-related injuries and deaths indicate the same underlying problems — a punitive culture that can endanger firefighters’ health, a lackluster physical screening process and an ineffective plan for building up firefighters’ tolerance for heat.

On the day of Katkov’s hike, Cal Fire officials later found that his captain, Joe Ekblad, had missed opportunities to act on several telltale signs of heat illness. Not until Katkov collapsed at the top of that ridge did Ekblad begin emergency procedures.

The captain later explained he believed that they could cool Katkov down if they moved fast enough. They stripped off his jacket and drenched him in water. But it didn’t work. Katkov took several deep “gulpy breaths,” according to documents obtained from the state’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health, known as Cal/OSHA. Still, Ekblad delayed calling for emergency help because he thought Katkov “would snap back out of it,” the records show.

Katkov died of hyperthermia at a hospital the next day. Cal Fire demoted Ekblad. The department found he had “failed to identify a crew member ... in physical and/mental distress.” Ekblad didn’t respond to requests for comment. Records show he told investigators that Katkov was a willing participant in the exercises.

Cal Fire didn’t respond to several requests to interview the department’s head of safety. In a statement, it said it “vigorously rejects the notion that a punitive culture exists in relation to the fitness, safety, or wellbeing of our workforce.”

The department says it trains all its firefighters — seasonal, incarcerated or otherwise — on the dangers associated with wildland firefighting, “including methods to prevent, recognize and respond to symptoms of heat related illnesses.” It described its efforts to combat heat-related injuries and deaths as “a partnership” with individual firefighters.

“Each must do his/her part year-round to ensure that they are preparing for the upcoming fire season,” the department wrote.

Signs of heat illness not recognized

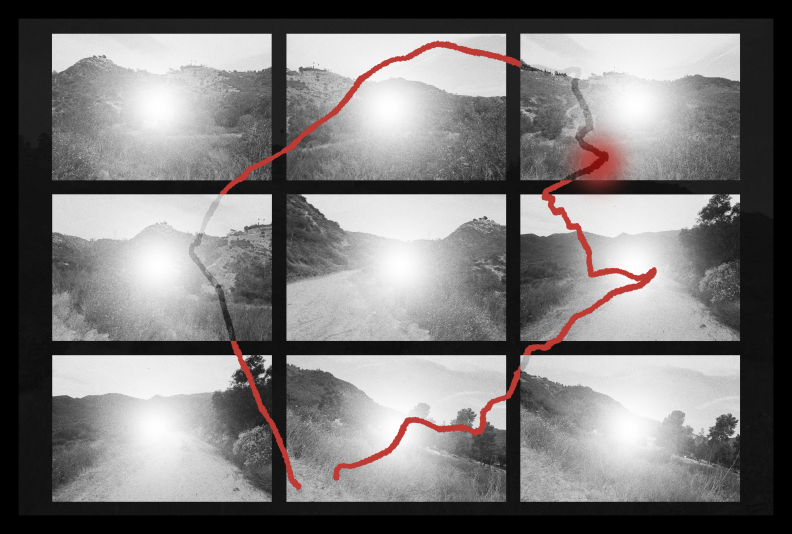

On July 28, 2019, Katkov embarked on a training exercise called the Lippe Hike, a 1.45-mile loop at Cal Fire’s Station 16 in Fallbrook, California, a mountain town ringed by ranches just outside of Temecula.

Gavin Bledsoe, one of the station’s other fire captains, later told Cal/OSHA investigators that “he had concerns with Joe pushing Yaro hard,” and that Ekblad had pushed other firefighters without giving them enough time for breaks in the past.

According to documents related to Ekblad’s demotion, the hike that preceded Katkov’s death had never been timed before that morning, and Bledsoe believed the standard for finishing it was set “specifically with Yaro in mind.”

“Joe has been pushing really hard to get Yaro to quit or up to his standards,” Bledsoe told Cal/OSHA investigators about the rookie firefighter who regularly hiked the area.

Bledsoe didn’t respond to multiple phone calls and text messages seeking comment.

A quarter-mile into the hike, seasonal firefighter Matthew Guerrero told investigators, Katkov was breathing heavily. At one point, as the hike wound from mountains alongside a road, Katkov was slow to move out of oncoming traffic.

Ekblad wrote in his notebook, “Road Hazard - Cognitive Question.” This was an early sign of heat illness that Ekblad ignored, Cal Fire documents show.

The trio completed the hike in about 40 minutes — 10 minutes slower than the time Ekblad had set for the station that morning.

“We're gonna do it again. The first hike was unacceptable,” Ekblad said, according to the Cal/OSHA investigation.

Ekblad later told the agency’s investigators that doing the hike twice wasn’t standard practice. Cal Fire concluded that it was “clearly unnecessary” given the signs of distress Katkov had exhibited.

The trio rested for 20 minutes, drank some water and set off to do the hike again. By then, the temperature had climbed to nearly 88 degrees — five degrees hotter than the 40-year average for the area.

On the steep, often-shadeless path, Katkov told Ekblad he was exhausted — another symptom of heat illness that Ekblad should have recognized, Cal Fire documents said. Rather than seek emergency care, however, the captain encouraged both firefighters to press on, and they pushed up the hill. Guerrero helped steady Katkov’s balance, but Katkov stumbled and had to pause at least 20 times.

Atop the 650-foot ridge, Katkov fell forward and sat down. Ekblad told him to take off some of his wildland gear, and Guerrero tried to shade him with a jacket. They poured water on him, but his eyes rolled back. He eventually passed out.

Nearly an hour after starting the hike a second time, Ekblad called for help. Katkov began to shake uncontrollably. It took another hour for an air ambulance to get to the remote location and transport Katkov to Temecula Valley Hospital. He died the next day.

Cal/OSHA inspectors found that Cal Fire:

- Hadn’t provided enough water or shade on the hike.

- Failed to monitor Katkov for pre-existing sensitivities to heat.

- Didn’t prepare Katkov for the intensity of the job, as required under Cal Fire’s heat-illness prevention plan.

- Didn’t initiate an emergency medical response until it was too late.

Cal/OSHA fined the department $80,875 — almost five times the average Cal/OSHA fine of $17,000 for all types of cases.

Ashley Vallario, Katkov’s longtime girlfriend, said she was shocked after reading the investigation. It was clear that Cal Fire hadn’t done everything it should have done to protect Katkov, she said. Its safeguards against workplace heat appear to have failed.

“They told me that everything that could have been done was done, and that there was no waste of time,” Vallario said. “I believed them.”

Cal Fire didn’t respond to written questions about Katkov’s death.

Cal Fire’s ‘toughness’ mentality

Rank matters at Cal Fire. Impressing superiors can help a seasonal firefighter move on to a coveted full-time spot. But a tough paramilitary culture often pushes Cal Fire employees to their physical limits, even in hot temperatures.

In many cases, that culture has contributed to serious heat-related injuries.

In 2013, for instance, a Cal Fire firefighter was at a “rehire” training session in Riverside, meant for seasonal employees about to rejoin their crews. He and the other trainees were forced to do “extra rigorous” exercises after someone had arrived late, according to a Cal/OSHA investigation. While the group practiced a simulated fire attack, the firefighter complained about feeling ill and asked his supervisor if he could take off his jacket.

The instructor said no and told the firefighter to sit down in the sun, the records show.

About 10 minutes later, a colleague reported that the firefighter did “not look good.” His legs cramped, and he was gasping for breath — both symptoms of heat illness.

The firefighter was hospitalized for two days, and Cal/OSHA fined the department $18,560 for violating California’s heat standard by failing to allow the employee to take an adequate rest break.

In a similar case in 2017, another Cal Fire firefighter was working in full wildland gear while moving a hose for a training exercise, according to Cal/OSHA records. After a break, a new instructor took over another round of the activity.

The firefighter later told Cal/OSHA that the work was more strenuous the second time, and that the instructor had “pushed the employee to do more.” The firefighter struggled to finish the task. He was so confused that he couldn’t answer questions, Cal/OSHA records show. An altered mental state is a red flag for heat illness, medical experts say.

The instructor mocked the firefighter and suggested he “go to Orange County since their training is easier,” the inspector wrote.

As in the earlier case, the firefighter spent two days in the hospital. Cal Fire was fined another $2,430 for failing to educate employees about heat’s threats and not providing ready access to water and shade.

Cal Fire Battalion Chief Jon Heggie, who leads several fire stations based in San Diego, including Katkov’s former station, said the department is working to root out the “toughness” mentality that has pervaded its ranks. Some heat-related incidents “have been an unfortunate wake-up call that maybe that culture needs to change,” he said.

But that may be difficult. Robert Salgado, a former Cal/OSHA inspector and wildland firefighter, notes that Cal Fire’s do-or-die attitude is one of the “very deep-rooted cultural practices in the fire service” that is passed from department to department.

“We don’t want the smartest guy … we don’t want the most trained guy,” Salgado said. “We just want a guy who can throw on a pack and hike hills.”

Cal Fire union president Tim Edwards recalls a recent incident in which supervisors pushed firefighters in training activities beyond their limits.

“I’ll admit it, we had problems in San Diego in the last four months,” he said, explaining that one supervisor was warned about the way he was treating firefighters after a union member had filed a complaint.

The supervisor was pushing firefighters to hike “when they weren’t feeling good,” Edwards said, “making them hike thinking if he pushed them a little bit further, it would help them.”

Cal Fire, for its part, acknowledges that the department spoke with the supervisor but said he was not reprimanded. It describes the incident as an example of how the department and the union can work together to address potential health issues before they get worse.

‘Don’t blame the firefighters’

Another problem, insiders say, is that Cal Fire doesn’t have a physical fitness standard that makes clear what kind of shape seasonal and incarcerated firefighters must be in when they return to duty after months off.

Without such a standard, firefighters may not realize they’re not fit enough until they’re on training hikes or in the field on hot days. At that point, it’s up to individual supervisors to say whether it’s a problem for any firefighter, and what that firefighter needs to do to improve. And that can make for trouble when those supervisors push their employees too hard, even on hot days, to reach whatever level they deem correct, insiders say.

Edwards, of Cal Fire Local 2881, notes that the union has “been pushing for years to have a minimal physical fitness standard.”

He said the union wants seasonal firefighters to have their fitness tested over a week, with intense physical exercise and step-by-step goals to measure their progress. If they fail to pass those tests, he said, they could be set on a remedial path or let go.

Edwards blames the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation for issues involving incarcerated firefighters. He argues that Cal Fire has little control over these abilities when they arrive at fire camps, even though the 11 heat-related incidents involving incarcerated people identified by CJI and LAist occurred during official Cal Fire trainings.

The Corrections Department said Cal Fire has always trained incarcerated firefighters.

Currently, when a firefighter falls behind on fitness requirements, Cal Fire’s system leaves it up to individual stations to determine how that firefighter will move forward.

When firefighters are assigned to a crew for the season, they are allotted an hour each day for personal training, and given access to wellness coordinators and workout gear. Supervisors are required to sign off on each firefighter’s monthly progress as part of a “Physical Fitness Documentation Log.”

In more than half of heat-illness cases examined by CJI and LAist, the firefighters didn’t have a fitness plan.

In interviews with a Cal/OSHA investigator, some of Katkov’s former colleagues raised concerns about his physical fitness.

But Cal/OSHA found that Ekblad had not created a fitness plan or any documentation to measure Katkov’s progress, records show.

In its statement, Cal Fire said it has no control over its firefighters’ “fitness efforts, caffeine intake, eating habits, water intake, sun exposure, alcohol consumption, or other factors that may impact their ability to perform their job functions” when they are off-duty.

It can take weeks or months for firefighters to safely build up their fitness, and experts say it’s not something that can be forced with strenuous exercise in a short period.

“Just as a runner cannot expect to run a marathon without months of preparation, a firefighter cannot show up for the beginning of fire season . . . without preparing their body for the tasks ahead,” Cal Fire said in its statement.

Brent Ruby, a University of Montana professor who has studied the physical demands of wildland firefighting, said ad hoc training is not the ideal way to train because there’s “a tendency to try to push” new or young recruits. As these firefighters press on, he said, the strain on their body builds up.

“They hike faster, they produce more heat,” Ruby said, “but the environment is still bearing down on them and pushing back on them.”

Dr. Thomas Ferguson, a consultant who says he reviews 8,000 medical files for Cal Fire each year, has seen how firefighters who are pushed too hard can get blamed for not meeting physical expectations.

Ferguson told Cal/OSHA investigators that seasonal firefighters like Katkov are most vulnerable to heat illness. According to Cal/OSHA’s investigative file on Katkov’s death, Ferguson urged the department to adopt a fitness standard for seasonal and incarcerated firefighters partly for this reason.

“Don't blame the firefighters,” he said in a recent interview. “We've got to educate the supervisors to recognize that they need to pay attention to this.”

‘A better physical playing high school football’

Even before starting the job, Cal Fire’s health screening processes may miss conditions that could jeopardize firefighters’ lives, experts say.

Seasonal and incarcerated firefighters get little more than a basic physical, which experts say doesn’t always screen for potentially problematic health conditions. That has had dire consequences on the ground. Since 2001, eight firefighters with underlying health problems have died during training — five of them likely from heat exposure, experts say. All of them were incarcerated except for Katkov. Four died from cardiovascular issues, such as heart attacks.

While not all of those cases were directly tied to heat, researchers say high temperatures often play a hidden role in injuries and deaths, especially in workers who have underlying or pre-existing health conditions, such as heart or kidney disease.

Cal Fire said its screening policy requires “an annual medical evaluation for all applicants and employees who are required to be medically cleared.” Tests intended to check for pre-existing conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders and some cancers, are voluntary.

In a recent interview with CJI and LAist, Ferguson said Cal Fire has a hard time keeping up with the basic screenings for thousands of seasonal and incarcerated firefighters each year. “It’s an operational issue for them,” he said.

The union’s Edwards goes further. “When the State of California is hiring a temporary employee, and this is just the sad truth of it, they're not going to want to invest a whole lot of time and money,” he said. “We don't agree with that.”

It’s not until age 40 that full-time Cal Fire employees are required to take heart and blood tests, according to the union. Seasonal firefighters are offered the opportunity, but it’s not mandatory.

Heart issues, which could be caught by more extensive tests, are among the preexisting conditions exacerbated by heat. When a firefighter dies, heat can be overlooked as the primary factor, creating a pattern of uneven enforcement, records show.

In April 2015, Raymond Araujo, a 37-year-old incarcerated man assigned to work in the Bautista Conservation Camp, set off on a training hike in Banning, California, about 30 miles from Palm Springs. According to Cal/OSHA records, Araujo covered two miles of steep terrain. The temperature reached 81 degrees — 10 degrees hotter for the area for that time of year. He stumbled during the exercise. His colleagues tried to carry him to the finish but eventually he lost his vision and fell to his knees. About an hour after the hike began, paramedics declared him dead, according to the records.

A Cal/OSHA investigation named heat as a contributing factor in Araujo’s death, but the Riverside County coroner determined the cause was “hypertensive cardiovascular disease,” according to an autopsy report. Cal/OSHA’s medical unit, noting the pre-existing condition, concluded that “it did not appear likely that a heat illness or other work-related illness or injury played any role in Araujo’s sudden death,” records show. The agency closed the case without issuing any citations for violating the state’s heat standard.

Garrett Brown, a Cal/OSHA inspector from 1994 to 2014, investigated more than 100 work sites for heat issues. He reviewed the Araujo case at our request and said it was impossible to know why the agency chose not to address the heat standard violations. Despite that decision, Brown said the incident resembled many heat cases he had handled, in which workers suffered heart or kidney failure because of hot temperatures, and likely should’ve been handled as possible heat standard violations.

A Cal/OSHA spokesperson defended the agency’s handling of Araujo’s death. “Cal/OSHA Enforcement relied on the Medical Unit's opinion,” the spokesperson, Frank Polizzi, wrote in a statement.

Ferguson isn’t the only one who’s raised concerns about Cal Fire’s health-screening process. During the Cal/OSHA investigation into Katkov’s death, Tammy Stout, manager of the Cal Fire medical unit, was blunt in her assessment of the process, explaining that she had received medical clearance even though she believed she was physically incapable of doing a firefighter’s job.

Cal Fire Captain Cesar Nerey put it simply. “You could get a better physical playing high school football than the one required by Cal Fire,” he told the Cal/OSHA investigator.

The pinnacle of heat awareness

There’s another concerning factor in how Cal Fire brings new firefighters onto the job: a lack of a department-wide regimented acclimatization plan that would ease employees into the heat. Instead, as with fitness training, Cal Fire leaves it up to individual stations to craft their own.

Here’s why that matters. Acclimatization — building up a tolerance for heat — is a crucial part of training firefighters to operate in extreme conditions.

Easing firefighters into the work in hot temperatures is widely viewed as one of the best ways to prevent heat illnesses and deaths. It should happen during a new or newly returned firefighter’s two weeks of training, health experts say.

For nearly 25 years, since the death of a California firefighter from heat exposure while constructing a fire line in 1997, a federal agency has recommended the state follow specific protocols for acclimatization of firefighters.

The protocols, from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), call for:

- New employees working in heat no more than 20% of their first shift, with a daily increase of the same percentage until fully acclimated.

- Experienced firefighters returning from an extended break working in heat more than 50% of the first day, with a gradual increase over the course of a week.

Cal Fire said that it is considering those recommendations, but it “may not be achievable in all situations.”

The department said following them “could cause issues in protecting the people and resources of California,” since firefighters often are thrust into emergency situations when a fire erupts and may come from areas across the state and be used to different climates. Cal Fire did not address non-emergency training scenarios.

Some heat-related incidents have occurred early in a firefighter’s tenure and during training. Of all the incidents identified by CJI and LAist, records show at least 14 employees were sickened by heat at the Cal Fire training academy during their first weeks. Dozens more suffered from heat illnesses on the job. Over a two-month period in the summer of 2014, three firefighters were hospitalized after they had trained in the heat. Two of these incidents occurred in the same week.

Cal/OSHA considers an acclimatization plan the pinnacle of heat awareness — indeed, it is one of the four pillars of heat safety in the state’s standard. Yet the agency leaves the details on how to acclimate employees up to individual employers.

In a written statement, Cal/OSHA said “the acclimatization period, when employees are introduced to high heat, is the most critical in terms of illness prevention.” The agency rarely cites employers for failing to acclimatize their employees, as compared to other heat related violations, having done so only 68 times since 2015, as of July 2021.

While heat continues to be an issue during Cal Fire training activities, a responsive supervisor can make the difference between life and death.

Nearly a year after Katkov’s death, yet another firefighter came close to dying on a training hike in Mariposa, 150 miles east of San Jose. The firefighter had suffered leg cramps and vomited on the same trail just two weeks earlier, according to Cal Fire documents. A physician cleared him for work, but people with prior injuries can be more susceptible to heat stress, experts say.

On a hike in July 2020, the temperature reached 87 degrees. According to Cal Fire records, the captain, who said he’d been aware of the firefighter’s medical issues, watched his progress during the 60-minute exercise. When the firefighter gasped for breath, the captain implored him to slow down. When his legs cramped, a colleague helped him down a hill. The captain called an ambulance, and the crew gave him oxygen. Airlifted to a trauma center, he was treated for heat stroke and a heat-related condition known as rhabdomyolysis, which causes muscle tissue to break down and leak toxins into the blood.

Ashley Vallario, Yaroslav Katkov’s partner, who considered filing a lawsuit but decided against it, still can’t understand why Katkov wasn’t given the same level of care.

Katkov was selfless, she said, someone who would help others even to his detriment. Early in their relationship, Vallario remembers Katkov taking her on a date to pick up trash on the beach. Initially, that gave her pause, but she’s come to realize it was Katkov’s way of giving back. “It definitely made me, like, a better person,” Vallario said.

Since Katkov’s death, she has pushed Cal Fire to demand more of its leaders.

“You're supposed to have faith that those people would keep them safe,” she said. “It shows what kind of leadership that they're willing to allow.”

-

The recounting of events leading up to Yaroslav Katkov’s death is based on interviews with a half dozen current and former firefighters, Cal Fire’s letter to Captain Joe Ekblad about his demotion, its internal investigation and a 378-page Cal/OSHA investigation that included a review of the station’s heat policies and interviews with eyewitnesses.

-

Brian Edwards reported this story as a fellow for Columbia Journalism Investigations, an investigative reporting unit at the Columbia Journalism School in New York, along with Jacob Margolis, a science reporter at KPCC and LAist, and a member of The California Newsroom. Adriene Hill, managing editor of The California Newsroom, Kristen Lombardi, investigative editor of CJI, and Megan Garvey, executive editor of KPCC and LAist, edited the piece. Caitlin Antonios provided fact checking services. David Nickerson, a reporting fellow at CJI, Robert Benincasa, a senior data reporter at NPR, and Cascade Tuholske, a climate impact scientist at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, contributed to the data analysis. Public Health Watch, an independent investigative nonprofit news organization, also helped produce this story.

This story was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.