On a recent triple digit summer day, I made my way out to a dusty field at UC Riverside, the research center of California’s citrus universe.

Row after row of tangerines, oranges and pomelos —11,000 in total — baked under a heat dome. Off in the distance, wildfire smoke passed in front of the San Bernardino Mountains, which had been covered in thick snow just a few months ago.

The dusty field is just one of the many plots that the university uses to trial new trees, grow budwood for distribution and come up with solutions for devastating problems like Huanglongbing, a bacteria driven greening disease that’s threatening trees world wide.

However, I was there to check out a block of 48 trees sitting along a fence that look nothing like the thousands of citrus around them. Inconsequential at first glance, you could easily imagine them along any road in Los Angeles, but that’s kind of the point. The trees are being tested to see if they can survive our hellishly hot and dry future driven by climate change.

Where, how and why these trees are being tested

It’s a collection of 12 different species — four of each — pulled from around the world and being run through the gauntlet by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Planted seven years ago, they were given supplemental water to help them get established, but since then they’ve had to survive on their own through record-setting heatwaves and drought years.

The trees are being assessed for a number of factors including attractiveness, whether they provide good shade, how much work it takes to maintain them (less pruning means lower maintenance costs) and whether they can survive without much water.

The experiment is expected to run for at least 20 years, but visit the plot today and it's clear which trees are thriving. Surprisingly, just because a tree comes from a hot climate doesn’t mean it’s going to do well.

“What kind of choices are we going to be able to make in the future?,” said Natalie van Doorn, U.S. Forest Service scientist and co-creator of the experiment known as Climate Ready Trees. “Are we going to have enough water to make that decision that yes we want to keep watering our trees?”

If not, we’ve got to have viable candidates that we know will thrive and provide critical tree cover, which for residents, can be a matter of life or death.

Why L.A.'s hundreds of thousands of trees matter so much

Trees are an absolutely critical part of our infrastructure. They have a marked impact on human and ecosystem health.

Trees can:

- Help drop temperatures in urban areas by as much as 45 degrees

- Reduce energy use

- Suppress noise

- Improve air quality

- Sequester water

- Help provide homes to all sorts of creatures, all according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Which is why any sort of major threat to the more than 700,000 street trees planted across the city of L.A. is of major concern, and that's what climate change is doing.

Much of our urban forest, as it’s known, was planted over the past 100 years as the region developed. As people migrated from other parts of the country they often wanted to plant the trees that they were familiar with, though that could mean species from wetter climates.

The sweetgum tree, whose spiky seed balls you’ve likely stepped on while walking through a park, is a decent example. It’s originally from the eastern area of the country and doesn’t love drought conditions, thriving in the moist soils of the Mississippi Delta. More than 25,000 of them are planted across the city, according to a tree inventory.

“I think in general, many of urban forests contain what I would call legacy plantings that occurred after World War II, when people were building homes and moving in and planting trees. And so those trees now, maybe 40, 50, 60 years old, they were planted when water was abundant. They've grown accustomed to having water and of course they're not necessarily as well adapted to hot dry conditions,“ said Greg McPherson, retired research scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, and one of the creators of the experiment.

We were long able to satisfy a broad range of moisture requirements because we imported and dumped all but unlimited gallons of water all over our landscapes, often in an effort to keep our lawns green.

That is until this past decade, when drought and water cuts became the norm.

What happens to water-stressed trees

Water-stressed trees are more susceptible to pathogens and insect attacks, and are, predictably, more likely to die than healthy happy trees. One only need look to the Sierra Nevada to understand how bad things can get. More than 100 million trees have died over the past decade in part due to drought stress.

There are no clear mortality estimates for LA’s urban forest over the past decade, so we can’t say whether extreme conditions have led to more tree deaths in our area. And unless we had a widespread, granular tree tracking program, it’s going to be tough to determine why an individual tree is lost.

There are hundreds of thousands of street trees across the city, and urban trees face all sorts of challenges trees in our forests don’t. Yard tools can damage them and lead to the introduction of disease, poor pruning practices can lessen tree resilience and sometimes people just cut them down because they want to redo their yards.

That said, conditions are becoming more challenging for our urban forest and we could be on the path to greater die off as a result. Longer, more sustained droughts are becoming more common, meaning less water for irrigated landscapes, and more extreme heat days mean trees require more water to survive.

Odds are we haven’t seen the worst of it. Even though we’ve had a handful of water cuts over the past decade, lawns are still green and trees still often getting supplemental irrigation.

Given how bad cuts got before this wet year, it’s easy to imagine a point where outdoor watering is limited to the point that lawns start to finally die off and the trees that rely on that same supplemental water start to die too.

“The roots of those trees are near the surface because turf is irrigated in frequent, but not heavy doses. So the water stays in the upper surface of the soil and that’s where the roots are,” McPherson said.

Depending on the variety, trees can take decades to become established and provide meaningful shade. If we’re planting something today with the expectation that it’ll survive in the lawn-less future we’re charging towards, it’s important to find species that can thrive on minimal supplemental inputs.

Our need for more resilient trees

McPherson’s efforts to find what the experiment is calling ‘climate-ready trees’ began about two decades ago, when he recognized what the existential threat of warming trends could mean for our urban forests.

“I began in 1999 when I got a 18 wheeler full of desert trees from Arizona shipped up and planted them all around Sacramento and Davis, and really started evaluating their performance,” said McPherson.

Some, like the Palo Verde, even though it can thrive in hot climates, struggled.

“It just grew so fast that the top would outgrow the roots and it would blow over in our wind,” he said. “Some of them worked, some didn’t. But that led to the idea that we need to evaluate more species”

In 2015 he and van Doorn got a grant to begin trialing trees at a test site at UC Davis, and eventually along the coast in Irvine, and in the scorching hot environment of Riverside.

So which trees have been thriving?

Though the experiment still has a number of years to go, I made the trip to the Riverside plot because out of the two Southern California plots, I wanted to see which trees were doing the best in the most extreme conditions.

Many were thriving, but three stood out because they looked healthy, cast wonderful shade and were quite attractive. They’d be wonderful along any street.

The Red Push Pistache was the first to catch my eye in part because it had one of the thickest canopies and beautiful leaves. It’s originally from Arizona.

The canopy of the rosewood, originally from India, rivaled the pistache and the Desert Willow, native to the southwest, put out gorgeous pink flowers.

The Honey Mesquite, also native to the southwest, was covered in bright yellow flowers and teaming with so many bees that the whole tree appeared to vibrate.

The ghost gum, a type of eucalyptus from Australia was also well established. However, because of their oil content eucalyptus tend to burn violently in wildfires. Maybe not the best choice for fire prone locations. And the tecate cypress is native to the region and looks like it could be trimmed into a hedge. It's struggled a bit at the plot.

Then there were the ones that appeared to need more maintenance, like the Palo Verde, which I see planted in drought tolerant landscapes across the area. It can thrive in hot conditions, and with a bit of pruning it might’ve looked better. Problem is it didn’t provide much shade.

And, to me, the Texas Live Oak looked to be an outright failure, as they were close to dead. It's reportedly done better in cooler conditions at the team's other test site in Irvine.

Go see the trees yourself

Each tree in the private research plot has a counterpart located in parks across the region, in an effort to help determine how they do when they’re not babied.

“If you were looking at reference versus park sites, the reference sites are doing better as far as survivorship and growth. In the park sites there just is a lot of variability,” said van Doorn.

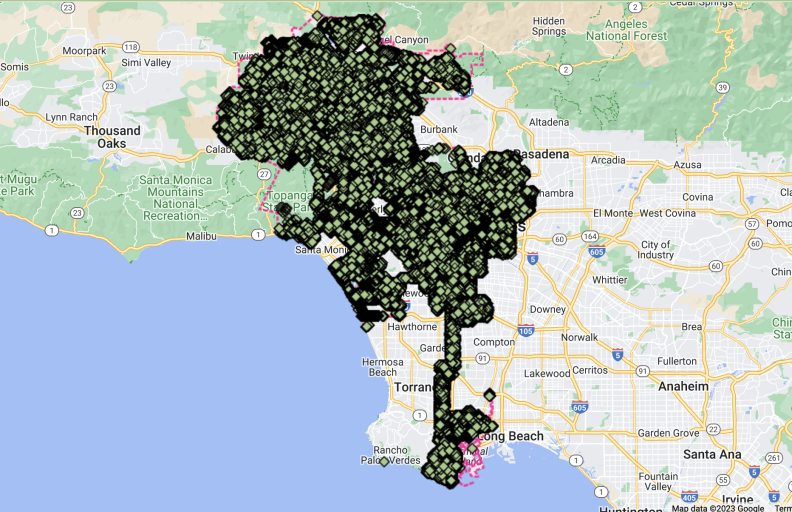

If you’re curious about how they’re doing, you can actually go visit them in person.

For instance, here’s a map of tree locations if you live near Woodley Park in the San Fernando Valley.

Or if you’re over on the west side, the trees might be performing completely differently at a spot like Vista Del Mar Park.

If you want a more granular look at all of the trees, the researchers issued an update three years ago here.

If you have any favorite drought tolerant trees, shoot me a note below.